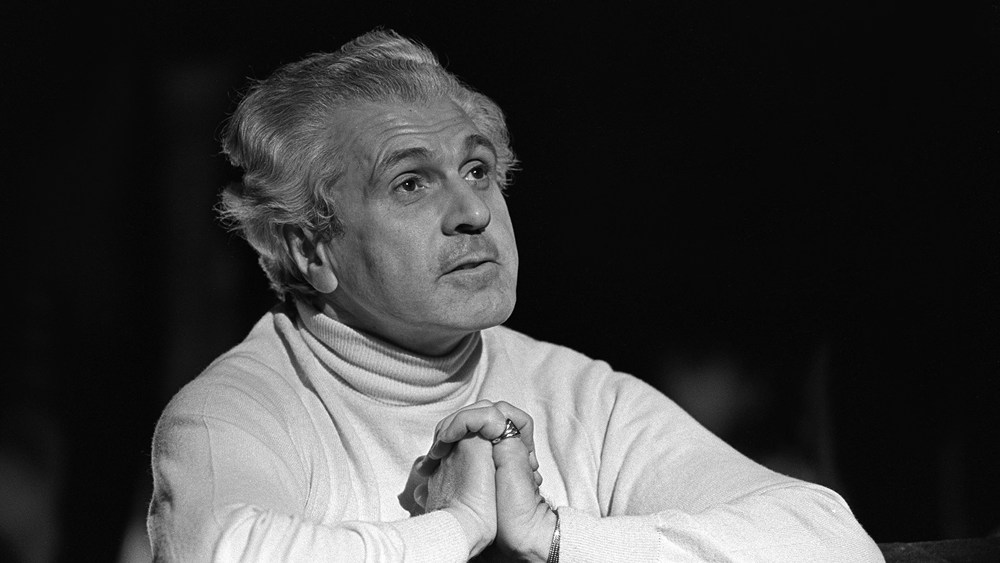

Remembering Julius Rudel

March marked the 100th anniversary of the birth of Julius Rudel, the general director and principal conductor of New York City Opera from 1957 to 1979, during the glory years of that company. Rudel came to the United States as part of the wave of Jewish musicians who emigrated during the Nazi era from Germany and Austria — quite a few of whom exerted a formative influence in the growth of American opera. Steeped in the aesthetics and practices of the European tradition, and eager to explore new ideas and technology in his quest to produce opera as “total theater,” Rudel was able to merge Old and New World values to bring youthfulness and dynamism to an art form long perceived as elitist and stodgy.

Under Rudel’s direction, City Opera presented innovative productions of familiar and rare works at affordable prices with an ensemble of homegrown singing-actors, generating goodwill and new fans across the country with tours and, beginning in 1976, the Live from Lincoln Center telecasts. It was Rudel who was at the helm of the company in 1966 when it moved 10 blocks uptown from its rather humble City Center quarters to the newly built Lincoln Center — where “the people’s opera,” on its shoestring budget, proceeded to provide a compelling alternative to the Metropolitan Opera across the plaza. NYCO pointed the way to the rise of regional opera companies, and in the years before young artist programs had arisen across the country, provided essential training to emerging singers.

Born on March 6, 1921, in Vienna, Rudel fell in love with music and theater as a youngster. He had vivid childhood memories of watching Maria Jeritza as Carmen escaping across a bridge, and of being taken by his mother to see the colossal Max Reinhardt production of Goethe’s Faust at the Salzburg Festival. Many of the productions that made a lasting impression on the schoolboy Rudel from his standing-room perch at the Vienna Staatsoper — especially Tristan und Isolde with realistic, romantic designs by Alfred Roller — had been put into the repertory in the first years of the 20th century by his idol Gustav Mahler.

Escaping the Nazis after Hitler’s annexation of Austria, Rudel came to New York in 1938. Five years later, newly graduated from the Mannes School of Music with a degree in conducting, he noticed an item in the morning papers about the formation of the City Center of Music and Drama, which would occupy the former Mecca Temple in Midtown Manhattan. As mandated by New York City Mayor Fiorello La Guardia, City Center would be a center of cultural activity, affordable to everyone. Rudel donned his best suit and made a beeline for the rather shabby building on West 55th Street, walking in unannounced, and talked his way into a job. He began his tenure at City Opera as a rehearsal pianist and all-around factotum three months before the company opened in February 1944, made his conducting debut there on November 25, 1944, with The Gypsy Baron, and rose through the ranks to the general director position 13 years later.

Rudel strongly believed there was no clear-cut divide between opera and musical theater and that, for the audience, there were just two kinds of music: good and bad. “Europeans grow up with music as an integral part of their lives, and as such it is popular, intended to be entertaining and fulfilling, not simply ‘art’ that is to be endured,” he said. “For Americans, the movies have served in this way, while serious music, especially opera, has had social and intellectual associations and pretensions. If ever this ‘snob’ barrier is to be broken down, opera must be brought to the people in a credible way with attention paid to dramatic values.” Shortly after taking over the directorship of NYCO, he came up with a plan to weave American works performed by American singers into the fabric of our cultural life: a plan that galvanized the arts world here and was followed with great interest abroad.

In April 1958, New York City Opera presented the first of three seasons of all American operas in inventive productions directed by Broadway’s Frank Corsaro, Margaret Webster, Carmen Capalbo, and José Quintero. The “American seasons” had the backing of Morton Baum, chairman of the City Center finance committee, and were produced with seed money from the Ford Foundation. Robert Kurka’s punch-packing satire The Good Soldier Schweik was given its world premiere during that first season and has since found its way into the international repertoire, and several other American operas that were presented, including Carlisle Floyd’s Susannah and Douglas Moore’s The Ballad of Baby Doe, became closely associated with City Opera over the years. After the American seasons had run their course, Rudel continued to seek out and commission new works — 15 in all ― bringing to the fore U.S. composers like Robert Ward (who won a Pulitzer Prize in 1962 for his searing adaptation of Arthur Miller’s The Crucible) and Jack Beeson (1965’s Lizzie Borden), and proving to the world that American operas can hold their ground with the European repertory.

City Opera was the first major opera company to break the color barrier. Under Laszlo Halasz, its first general director, it had cast Todd Duncan as Tonio in Pagliacci in 1945 and Camilla Williams as Butterfly in 1946. Its first world premiere, in 1949, was Troubled Island, by William Grant Still and Langston Hughes. (Rudel, incidentally, conducted the last of Trouble Island’s three NYCO performances.) Rudel continued that tradition. In 1966, he received an angry letter from a subscriber who objected to the casting of the Black soprano Veronica Tyler as Pamina in The Magic Flute. “How dare you have a mixed-race couple?” the patron asked. Rudel’s terse reply: “I chose the best available singer for the role. Besides, we have no idea who Pamina’s mother, the Queen of the Night, cohabited with.”

Rudel cast Beverly Sills in the defining roles of her career: The Ballad of Baby Doe in 1958, Cleopatra in Handel’s Giulio Cesare in 1966, and Donizetti’s three queens in the early 1970s. Ginastera’s Don Rodrigo, the contemporary work with which City Opera opened its new home at Lincoln Center’s State Theater in 1966, featured the young Plácido Domingo the plum title role of the tragic eighth-century Spanish king.

The electric bass-baritone Norman Treigle, whose career reached a high point in 1969 with his terrifying portrayal of the title role in Boito’s Mefistofele, was another home-grown NYCO talent. Treigle was part of a group of distinguished performers, including Frances Bible, Chester Ludgin, and Patricia Brooks, who chose to spend their entire New York stage careers with City Opera. The company’s strong ensemble work garnered acclaim for such diverse fare as Mozart’s Così fan tutte, Blitzstein’s Regina, Britten’s A Midsummer’s Night’s Dream, Shostakovich’s Katerina Ismailova (the Khrushchev-era version of Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk), and Debussy’s Pelléas et Mélisande.

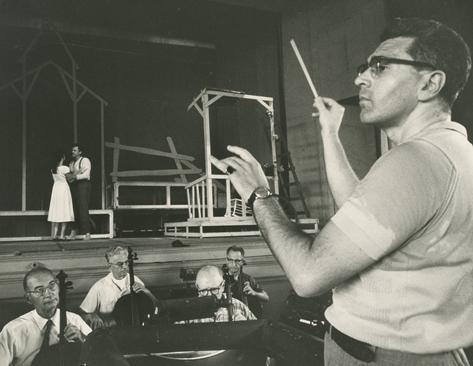

Rudel adored Brigadoon by Alan Jay Lerner and Frederick Loewe (“a fellow Viennese”) and anything by Kurt Weill — with whom he felt a special kinship, “not just because we were both Jewish refugees from the German territories, but also because we agreed that Broadway presented the wave of the future, the direction in which American opera was heading and the direction in which it should be heading.” Rudel brought three of Weill’s musical theater works into the repertory of New York City Opera, including Lost in the Stars (which he conducted, with Lawrence Winters and Shirley Verrett in her company debut as Irina) and Street Scene, during the American Seasons. In the 1950s and 1960s, he conducted acclaimed City Center Light Opera revivals of musicals like Brigadoon and Carousel with such rising stars as Barbara Cook, Edward Villella, and Merv Griffin; and he collaborated with Sting on the 1989 Broadway revival of The Threepenny Opera.

There was a special kind of magic — Broadway pizzazz, if you will — in the best productions of the Rudel era, thanks to the genius of Corsaro and Tito Capobianco, who were the two directors most closely associated with City Opera in the 1960s and 1970s and brought in distinguished guest directors like Sarah Caldwell. Harold Prince, whose first assignment was Ashmedai by Israeli composer Josef Tal in 1976, later wrote that Rudel “pulled me from Broadway to the daunting world of opera.” Prince also directed the American premiere of Weill’s The Silver Lake, starring Joel Grey, which Rudel conducted in 1980, a year after Sills succeeded him as NYCO’s general director.

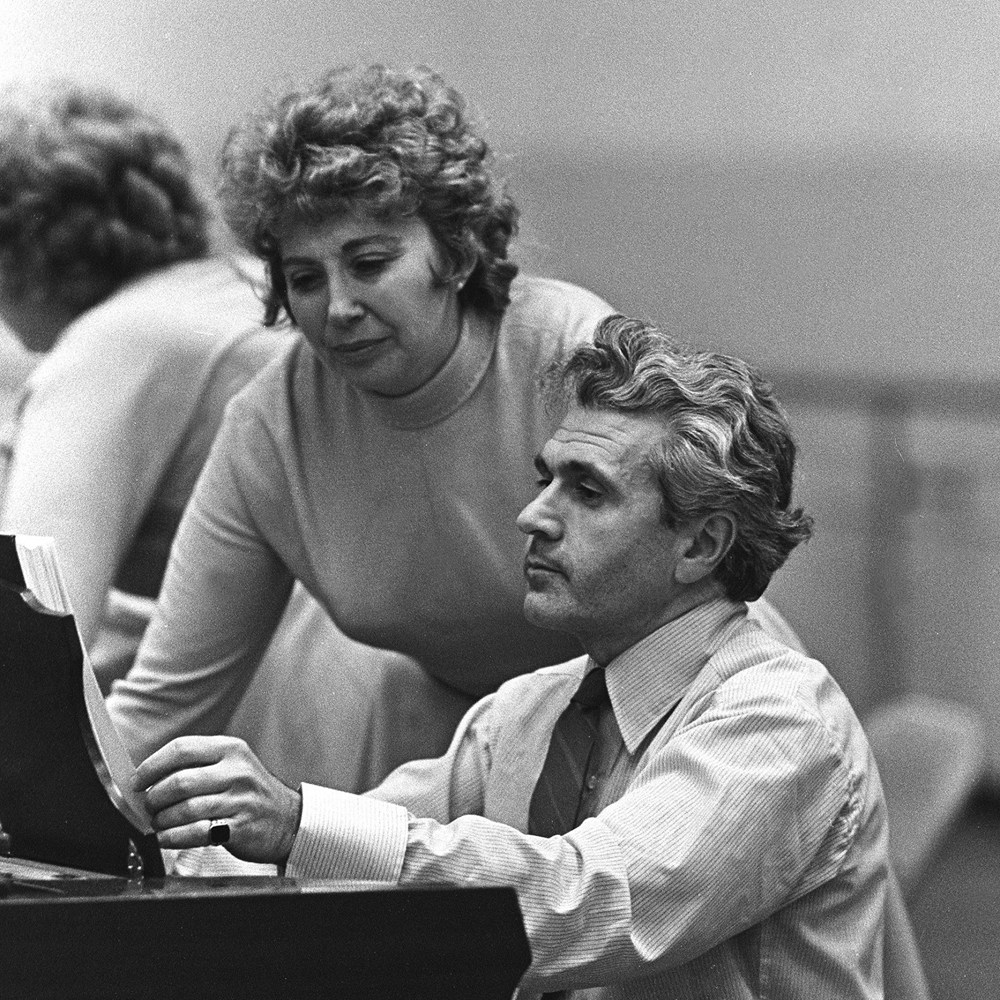

Rudel was a versatile, exacting conductor with an infallible theatrical eye. “He was always aware of what was physically happening onstage — pieces of business, scenery and props, and the emotional context of the scene,” said soprano Johanna Meier, which meant that he and the singers were truly “creating a performance together and not just being musically guided from the pit.”

Beverly Sills frequently spoke about the joy of rehearsing new productions with Rudel and the almost telepathic relationship she had with him during performances — “he seemed able to pre-guess me by about five seconds.”

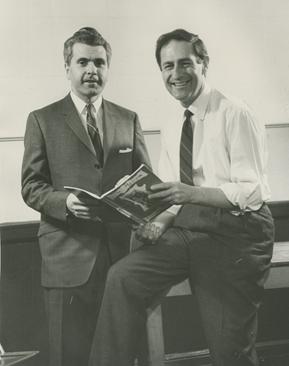

Bass-baritone Michael Devlin remembered Rudel as being supportive in the pit and nurturing of young artists: “The ‘Viennese Trio’ — Rudel, City Opera Managing Director John White, and Music Administrator Felix Popper — took special care not to push singers, even those who had a big talent. ‘I know you think you’re ready to sing a certain role, but let us be the judge of that, okay? You have to trust us on that!’ they would say to me. When I’ve seen so many of my friends going by the wayside, I realize that because the three of them were careful in the early years of my career not to push me or cast me in roles I was not yet ready for, they helped keep my career going for a long time.”

Rudel was also a master of multitasking. Concurrent with his duties at NCYO he took on the artistic directorships of the Caramoor Festival and, for a time, the Cincinnati May Festival. At the behest of Jacqueline Kennedy, he became the first music director of Kennedy Center, which opened in 1971 with Bernstein’s Mass.

In 1978, Rudel made his successful Metropolitan Opera debut conducting Werther. After leaving City Opera, he guest conducted frequently at the Met (268 performances in all) and at the world’s other leading opera houses and symphony orchestras — working with every major singer of our day, from Pavarotti to Anna Netrebko, and amassing a wide-ranging repertory unmatched by any other conductor. In 1999, he presided over the American premiere of Weill’s chilling 1931 opera Die Bürgschaft at Spoleto Festival USA. Rudel was 78 at the time, with the energy and boundless enthusiasm of someone half his age. He continued conducting for another decade, fittingly ending his public career with a return to two of his favorite American works. In 2008, fifty years after Rudel conducted Lost in the Stars at City Opera, he thrillingly conducted it again in a new production by Jonathan Eaton at the Virginia Arts Festival and Pittsburgh Festival Opera. Then in November 2009, at 88, he mounted the podium one last time at the newly renovated New York State Theater at Lincoln Center, now called the David H. Koch Theater, to lead a rousing performance of the Revival Scene from Floyd’s Susannah, joined by the City Opera Orchestra and Chorus and an old friend, the bass Samuel Ramey. There was not a dry eye in the house.

Two years later, when it was announced that City Opera, in dire financial straits, was leaving Lincoln Center and would perform in various venues around town, Rudel could not remain silent. He wrote a heartfelt, painfully honest op-ed piece for The New York Times lamenting the impending demise of his beloved company: “The board and management of City Opera cannot finance, produce, and support full seasons of new works and standard operas in interesting productions with first-rate casts as we once did.”

Following his death on June 26, 2014, The Telegraph wrote, “While musicians admired his clear direction in the pit, Rudel was the antithesis of the hot-tempered maestro,” and The New York Times obituary mentioned his “low-key personality” and the fact that “offstage, he never threw a tantrum.” That’s not quite true. Rudel was, at times, imperious and short-tempered, but only because he wanted every City Opera production and performance to be of the highest quality. He railed against the routine while forging a new identity for American opera companies and singers. Making good music, quite simply, was his life.

Rebecca Paller

Rebecca Paller has written about the arts for Vogue, Opera News, American Theatre, Opera, and Playbill and is the co-author of Julius Rudel’s memoir, First and Lasting Impressions.