Invisible Barriers

Three experts in equity, diversity, and inclusion — Roberto Bedoya, Mark Kent and Melanie Powell-Robinson — talk to Mark A. Scorca, OPERA America's president and CEO, about the impediments that can keep people of color away from attending opera. Hint: It isn't just ticket prices.

Melanie Powell-Robinson

Melanie Powell-Robinson is the executive director of Saint Louis’ Diversity Awareness Partnership, which acts as a catalyst to increase awareness and education about diversity and inclusion.

SCORCA: Opera Conference 2018 was your first opera conference. What impressions did you take away?

POWELL-ROBINSON: I really enjoyed meeting so many people who were dedicated to their communities and to making opera more diverse. After the sessions, people were excited to talk with me about ways to be more inclusive. Most recognized there was a need to evolve but were unsure of how to start. They were looking at the big-picture items, wondering, “How do I change a whole system?” But you shouldn’t focus on moving the big boulder; the question is, how do you take the incremental steps to make change — in your organization, in your community? Once those steps gain traction, you see that boulder move. Diversity needs to be verbalized by our leaders, who should be asking, “What are we doing to keep people from the outside from feeling included?” Then you have to stop doing those things. The change has to come from the top-down and the bottom up.

Your exposure to opera has been at one of the most accessible companies in the country, Opera Theatre of Saint Louis. Despite the connotations of snobbery and exclusivity that opera brings up, my guess is that you haven’t given up on us.

I certainly haven’t. I really enjoyed the experience, although it isn’t an art form I was exposed to in my youth. Many traditionally have not seen themselves reflected in opera, so they didn’t find a love for it early on. If you think about the ballet, there was a time when the African-American body was not seen as suitable for Swan Lake; it took some very intentional exposure and marketing before people could say, “I can see myself there.” A large number of minority-group members have disposable income that could support the opera, yet we find that they’re not necessarily turning up in droves to the art form. So is it only about the dollars, or is there something deeper?

My guess is you would answer the question that there’s something deeper, which probably relates to a sense of belonging, of feeling welcome, of not feeling like the “other.”

Absolutely. And it isn’t only race-related. Would a group of high school students feel comfortable coming in the way that they dress? Would they feel like they belong?

We point to operas like Champion, which OTSL did so well. And yet, I’ve spoken to some people of color who say, “I don’t want to have to wait for the opera that talks about the African- American or the Latino experience. I want to go to Carmen or La bohème.”

I agree. I think it’s extremely important to not segregate our market, thinking only certain topics will appeal to certain audiences. But we do want to see reflections of ourselves. We want diversity across all of the offerings. If opera really wants to change who sits in the audience, then it has to welcome diverse artists to represent all characters. Some say there is a shortage of diverse artists in the field, so we need to look at the talent pipeline. When we do, let’s not forget to include possible socioeconomic issues in the conversation. How do we develop artists and audiences in schools that don’t offer any exposure to opera? How do we continue to support minorities that find a love of the arts and want to climb up the ranks? How do we invest early in a diverse opera community both on stage and off?

Mark Kent feels strongly that the sense of otherness can relate to how any person of any color dresses and behaves. The socioeconomic barrier may be even stronger than the racial barrier.

I definitely think it’s layers upon layers. If I’m going to spend $300 to be entertained, why wouldn’t I choose to put myself in a space where I feel that I am included, where I see myself either in the art form or in the audience?

If there were one issue you wish we’d examine at our next conference, what would that be?

An exploration of continued conversation. When an audience has received the art form’s energy, what can we do to engage them in conversation? How do we get them not just to sit and receive, but to participate? Opera companies should be sending their staff, board members and volunteers out to create partnerships with community organizations and establish a safe space for people to communicate what may be differing philosophies.

Have you seen successful instances of this in other art forms?

At the movies, you see groups of people talking about what they just saw on screen. In universities, they dissect plays, movies, even hip-hop. How do you get dialogue opportunities like that for opera? Maybe there should be time for tea or wine and conversation to really break down some of the barriers. Maybe some of what feels like intentional exclusivity is simply that I don’t know the person next to me.

When you’re a newcomer at a church, you have to stand up and shake hands with the people around you. I personally cringe at that; then I wind up having really lovely conversations. I’ve been gifted with a sense of community and I go out smiling.

It is never comfortable to be the outsider — it’s like being 13 years old all over again. You think that you’re being watched and judged based on how you’re responding. I think it would be great to get more third graders into the opera house. Then maybe by the time that they’re in middle school or high school, the newness won’t feel so overwhelming. Sure, there are plenty of people at the opera who might resist the change, and not be interested in their new neighbors, but I believe that there would be a lot who would stay around and enjoy having a conversation with someone very different from themselves. I definitely think that there’s an opportunity for people who want to see diversity across all art forms to get involved and really help to be the change that we want to see.

Roberto Bedoya

Roberto Bedoya is cultural affairs manager for the city of Oakland, California. He is the lead consultant for OPERA America’s Civic Action Group, designed to build the field’s capacity for strengthening communities.

SCORCA: Did Opera Conference 2018 give you a sense of whether or not our industry is making progress toward greater diversity and inclusion?

BEDOYA: Well, first of all I want to thank OPERA America for being wonderful hosts. I still feel like a guest in your world, but I also feel like a familiar face. And yes, I think there is progress, which is in many ways linked to the Civic Action Group. You have created a cohort of leaders who are really keeping the issue of civic action front and center, and I think it’s having a ripple effect in the field. As we move down this path of diversity, equity, inclusion, civic engagement — there isn’t a magic bullet. The group is kind of figuring out what is hitting the mark and what is failing. How do we honor where we come from, and how are we going to move forward?

So you haven’t given up on opera as a medium for social progress?

You’re right. For instance, An American Soldier showed me that opera can deal with important social issues. I don’t work in the discipline, but I know there are young artists out in the world who are going to turn it inside out and create something different. There’s room to hit a refresh button to make opera speak to our time.

Putting the performing experience aside, what kinds of things can companies do to foster communications with their communities?

They should look for ways to make community connections outside of the performance experience. A word that they may want to reflect on is “publicness,” which is a little more porous than “community.” How does the community help set the boundaries for an opera company? The idea that civic engagement means “I’m going to get a bunch of colored kids to come in for music appreciation”— that’s the worst-case scenario. But if you’re mindful of your public charge and what publicness means, you have to deal with socio-economic issues; you have to deal with a variety of things. It could be neighborhood-based. It could be based around ethnicity. And they’re all legit, but the charge is to serve the public.

Mark Kent feels that in opera, a lot of what we interpret as racial inequity is actually more broadly about socioeconomic inequity. A rich black man wearing all the right clothes, with a beautiful wife wearing all the right jewelry, will feel welcome. Maybe “otherness” at the opera is defined more by socioeconomics than by race.

There’s some truth to that, especially since opera is such an expensive practice, and therefore attracts people of wealth. But I’m not going to back away entirely from race and racism and how it operates in social constructs. Sure, economics is a really important factor, but if you’re constantly denied a well-paying job because of your skin color, then you can’t afford the $150 ticket.

If you could prescribe for us the topic that we should really wrestle with, what would it be?

We need to look how “othering” works. It happens around race. It happens around gender. It also happens around economics. I’m not interested so much in the psychology of othering, but the sociology of othering. There might be some benefit for the field to think about their assets, space in particular, and how they can create relationships. Say you have a rehearsal space. What community group may need that space? It could be a kitchen for a homeless shelter. Those relationships need to be cultivated over time. You don’t need to make a big thing about it, but you can turn around and say, “Yeah, for the last 10 years, I’ve had a relationship with the soup kitchen.” I’m not asking people not to be what they’re about. But opera companies probably need to do a kind of an audit — not a financial one, but a look at their assets, and not be afraid to look at the demographics of assets — and then see what has potential for growth.

Regarding the psychology and the sociology of othering, what is it that has led us to accumulate the behaviors and pretentions that make other people feel unwelcome?

Everybody goes to ticket price right away, and that’s a barrier to access, definitely. The way opera is structured, you have rich people paying for it through voluntary contributions, and you have to make them feel special. And the way you make some people feel special is to “other” other people. We need to acknowledge the problem and then figure out collectively how we’re going to solve it.

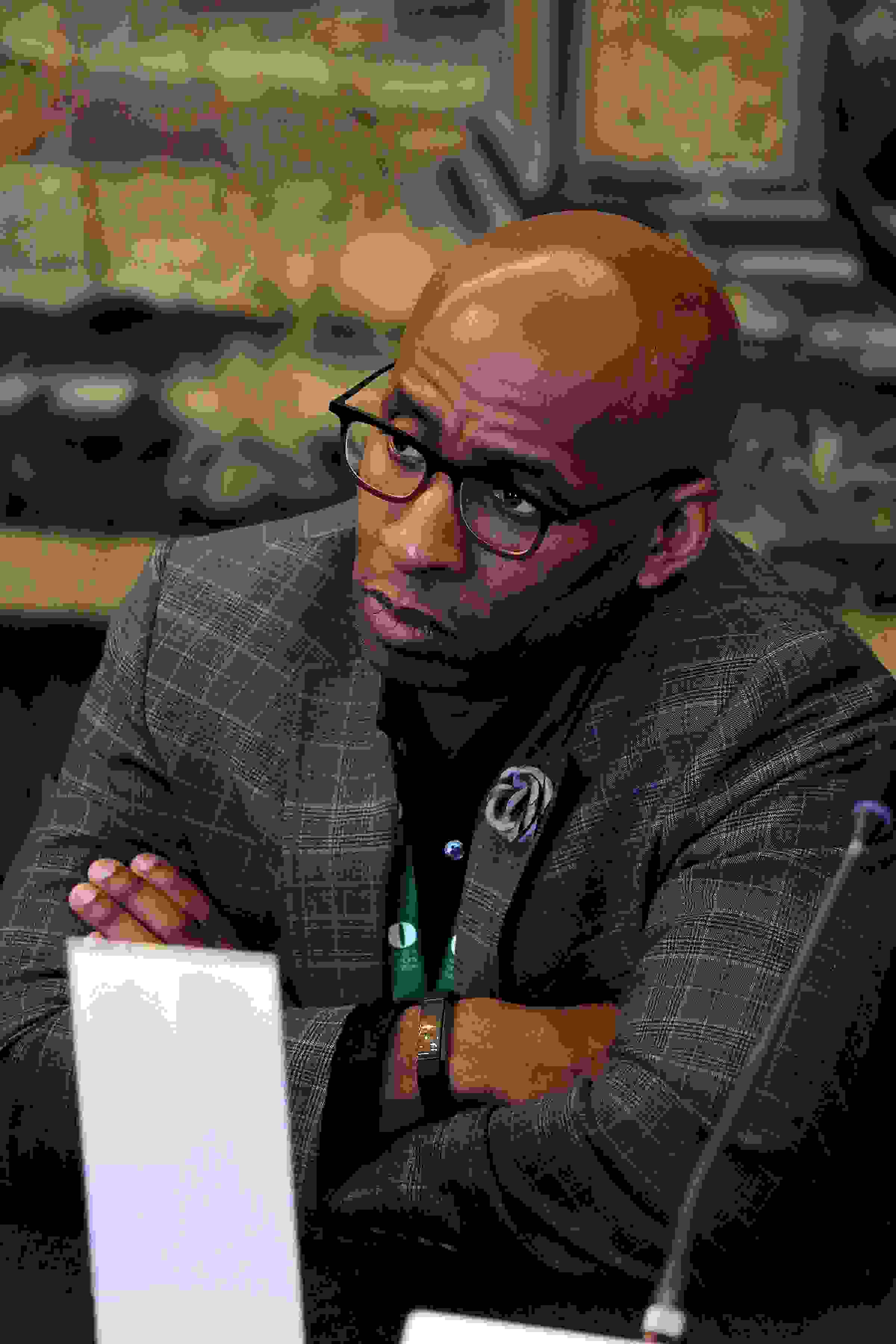

Mark Kent

Mark Kent is president of The Biome Foundation, the fundraising arm of The Biome School, a public charter school in St. Louis. He spent the first 10 years of his professional career as a baritone, performing with opera companies in the U.S. and abroad.

SCORCA: You’re involved with Opera Theatre of Saint Louis, you were a participant in the World Opera Forum, and you came to Opera Conference 2018. What has most surprised you about these experiences? I’m curious to hear how it was for you. Were you surprised or pleased or disturbed by anything in particular?

KENT: That everyone is afraid, and we don’t necessarily understand each other’s fears. We are fearful of losing our privilege, our status, our jobs and our safety; we’re fearful of poverty and law enforcement. These fears play into structural racism and fuel the lack of equity in all areas of people’s lives. I was also shocked to find that whites fail to realize that African-Americans share some of their fears, such as loss of status and jobs, and fear of the stereotypical criminal element.

Would it help if we all acknowledged our fears?

Yes, because fear brings out the worst in human behavior, and I think we see that really rearing its ugly head all over the world right now.

You’ve said before that a lot of what we think of as a racial divide is actually a socioeconomic divide.

Absolutely. What we see in the news is an image of all poverty being black and brown. In reality, there are many more poor whites in this country than there are poor African-Americans and Hispanics. It gets back to the idea that no one really wants to deal with the poor. We don’t want to live next to them. Although we may try to break down barriers for folks living in poverty, it’s always at a distance. It’s like “We want you to do better, we want you to get a great education — but until you’re wealthy enough, stay where you are.” If we really want to

move the needle, we’ve got to talk about how we bring people out of poverty and into the middle class. It will impact opera because when people are better educated, they are more likely to have jobs and the means to attend — they aren’t worried where the next meal is coming from — and then the audience will grow. But if you’re a young man on the streets, undereducated, with little to no prospects of employment, and someone walks up and says, “Hey, have you ever thought about opera?” — it’s kind of ridiculous.

If you could prescribe a subject to explore at next year’s Opera Conference, what would it be?

Without a doubt education, and how to make the arts a core part of every curriculum. That’s more important than the problems that are plaguing the arts — attendance and participation.

Those are in fact symptomatic of the larger issues in this country, and across the world, as well. You don’t have access to the arts if you are not educated. Education is key. It’s one of the few ways we can break the cycle of poverty.

But would it have been tone-deaf if, five years ago, we’d been talking to Ferguson High School about an arts program, when the school was so desperately in need of other things? Should we be advocating for fundamental resources before we turn our attention to arts? Or can we put arts on the agenda from the start?

It’s true, we should first advocate for educational equity. If you assign a student who’s not reading at grade level a Shakespeare sonnet set to song, that’s not going to work. You have to start small, because no one program can heal the ills of a city or even one neighborhood. So you choose a school to work with, and you form a partnership that’s going to last for a number of years, and you think, “How do we turn this school around?” The hope is to create a replicable school model that successfully integrates the arts.

So our overall focus should be not just on improving arts programs, but on improving schools — a somewhat less self-interested, broader approach to betterment.

Yes, absolutely. That’s the long game, because you won’t reap those benefits as an arts organization for quite some time. But if opera is to survive, if the arts are to survive, you must have an educated population.

This article was published in the Fall 2018 issue of Opera America Magazine.

Marc A. Scorca

Marc A. Scorca is the president/CEO of OPERA America.