My First Opera: Anthony Roth Costanzo

When I was six, growing up in North Carolina, I started taking piano, but I was really bad at sight-reading. So my teacher, Pei-Fen Liu, said, “Why don’t we try singing the notes from the page before we try playing them?” It turned out, I really liked singing. She started me on “Summertime,” and just a couple of years later I was doing shows in North Carolina, 15 of them over two or three years: The King and I, Gypsy, Winthrop in The Music Man. When I was 11, I told my parents: “I want this to be for real — I want to be on Broadway.” They said sure, and we flew to New York for auditions. I’d go to cattle calls with 500 children, and eventually ended up as the kid in the national tour of Falsettos. I did a bunch of shows for Playwrights Horizons and toured with Marie Osmond in The Sound of Music, playing various von Trapp children.

I had an opportunity to audition for Miles in Britten’s The Turn of the Screw at the New Jersey Opera Festival. I didn’t know anything about opera and I certainly didn’t understand the complexity of the music, but Michael Pratt, the conductor, said, “I think you can do it,” and he cast me. I had been singing in theaters for a while, so I sort of knew my way around. I also had a natural facility with the high stuff.

Turn of the Screw is a complicated story in its psychology: Is the Governess seeing the ghosts or hallucinating them? Have the children been abused? My parents, who taught at Duke University, are both psychologists, and my mother, Susan Roth, is a leading authority about post-traumatic stress disorder, specializing in child sexual abuse. We’d all drive down to New Jersey together and talk about what it’d be like for a child to be abused by his caretaker, Peter Quint, and the complicated relationship they’d have. It was a way for me to connect what I loved — singing — with what my parents did, psychology.

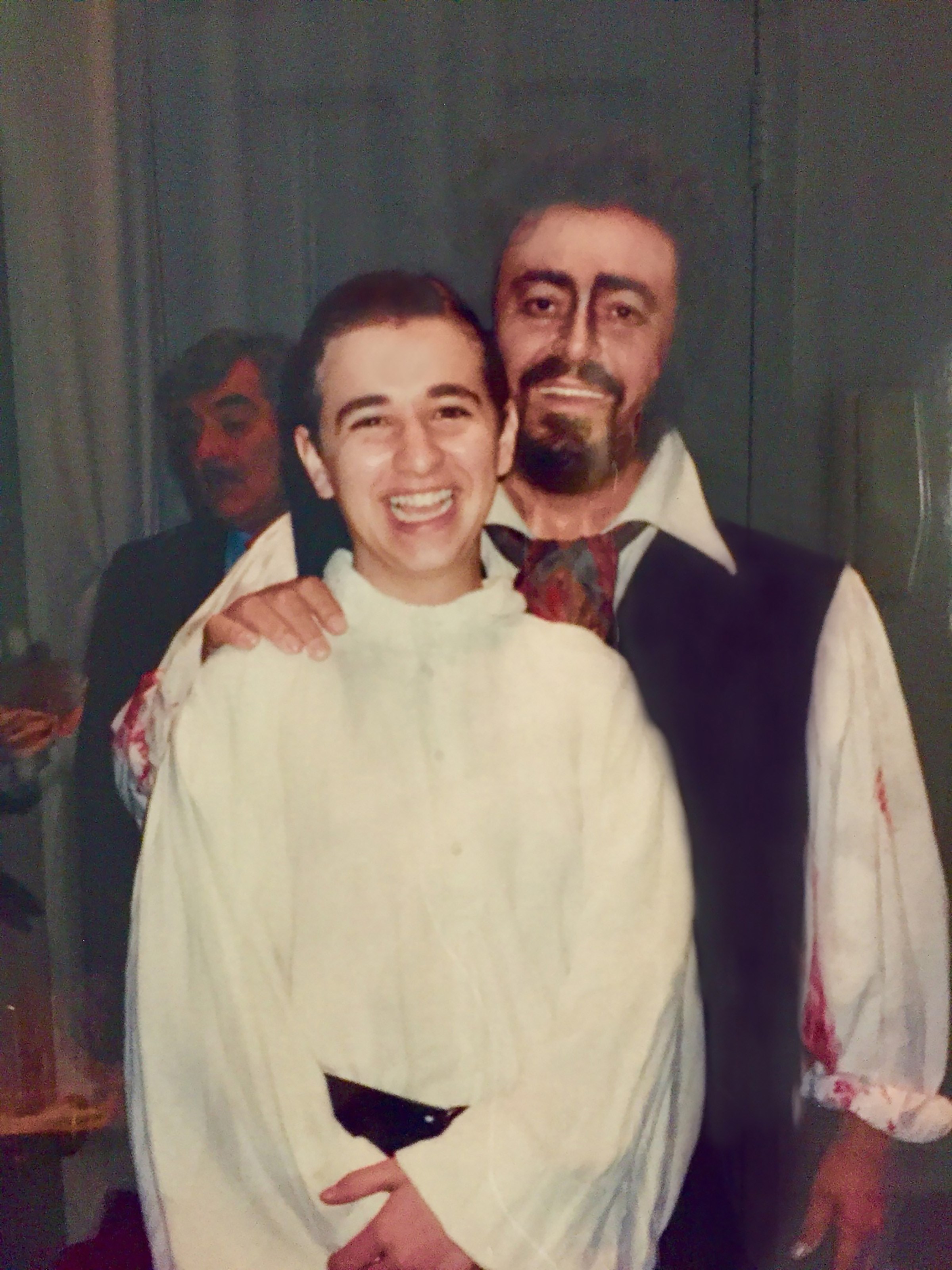

I began to understand what it was to sing opera. I got a manager, Anthony George, and he booked me into a gala performance at Luciano Pavarotti’s voice competition in Philadelphia, singing the Shepherd Boy in Act III of Tosca, with Pavarotti himself as Cavaradossi. After starting out in a strange modern piece, now I was going to the opposite extreme — touching the golden age, as it were.

When the show ended, Pavarotti arranged the curtain calls on the fly. I was standing there in my shepherd’s costume, and it seemed like I wasn’t going to get to go out there, but at the end he looked at me, stuck out his hand and took me out with him. Perhaps shrewdly, because he got a huge hand — everyone went wild. That was a very operatic experience.

I was 13, still singing soprano and not even thinking about it. But my colleagues were saying, “You already have hair on your arms; maybe your voice has already changed and you’re a countertenor.” I had no idea what a countertenor was then, but I began exploring. Pei-Fen had me singing all kinds of wacky material, from Liszt’s Petrarch sonnets to “Glitter and Be Gay.” I worked with Michaela Martens, who had been in Turn of the Screw, on bringing my head voice to middle C. When I sang for Steven Blier, he said I sounded like a screaming banshee, but he got me to work with Bejun Mehta, who in turn recommended me to his own teacher, Joan Patenaude-Yarnell. At first, she said, “No, no, no — I don’t babysit singers, thank you,” but after she heard me sing she said, “You’re sticking with me.” We’ve been together 20 years now.

The Marriage of Figaro was the first opera I ever saw as an audience member, in 1998 at the Met. I had already immersed myself in it: When I was cast in the film A Soldier’s Daughter Never Cries, James Ivory, the director, inserted a scene where I sang “Voi che sapete.” Later on, when I was 17, I ended up singing the whole role of Cherubino with Opera Santa Barbara. The Met Figaro had an amazing cast — Renée Fleming, Cecilia Bartoli and Bryn Terfel — and I began listening to their CDs avidly. I also went to performances with my countertenor idols: David Daniels as Sesto in Julius Caesar at the Met; Bejun as Armindo in Partenope at New York City Opera. (I later sang that role there myself.) I became obsessed with opera, but never as an outsider looking in. It was always as an insider making a career in the field.

Anthony Roth Costanzo's immersive operatic installation Glass Handel recently had its premiere during Opera Philadelphia's O18 festival and will be seen in New York in November. His debut solo album, ARC, was just released on Decca Gold.

This article was published in the Fall 2018 issue of Opera America Magazine.