Seismic Shifts

Five momentous decades have changed the face of the industry.

When OPERA America was founded in 1970, with 20 member companies, the U.S. was in the middle of an opera explosion. America had emerged from World War II with a new sense of its power and significance. Embedded in that burgeoning self-confidence was the drive to compete in the cultural realm, and cities large and small across the country began to create their own institutions to present symphonic music, ballet and opera. “It was in the ether — the idea that the arts were an essential ingredient of a strong, healthy country, and of a healthy community,” says Marc A. Scorca, president/CEO of OPERA America.

The venerable Metropolitan Opera was already a national presence, thanks to its radio broadcasts and extensive tour, and a handful of other opera companies were well-established in cities like San Francisco and Cincinnati. But in the 1950s and 1960s, the pace accelerated: Two dozen new opera companies were launched in major urban centers like Chicago, Dallas, Houston, Washington, D.C., Seattle and Minneapolis, as well as in smaller ones, such as Dayton, Madison and Palm Beach. In 1956, John Crosby founded The Santa Fe Opera, which would become the country’s biggest destination opera festival. The simultaneous founding of local and state arts councils, as well as the National Endowment for the Arts, created by an act of Congress in 1965, was a strong indicator that culture would now be a national priority. The resulting combination of new government support and the enthusiasm of civic-minded individuals, putting their skills and philanthropy at the service of the arts, spurred this dramatic new era of growth.

In the 1970s, the opera boom spread still wider and deeper into the American landscape, as more cities gathered the necessary volunteer leadership, resources and staff. Thirty-two of OPERA America’s current Professional Company Members were established in that decade, including Michigan Opera Theatre (1971), Des Moines Metro Opera (1973), Virginia Opera (1974), Opera Theatre of Saint Louis (1976), Long Beach Opera (1979) and The Atlanta Opera (1979). Founding stories varied. In St. Louis, the impresario Richard Gaddes, a John Crosby protégé, created his own version of the Santa Fe model, featuring operas sung in English translation. In Atlanta, the civic leaders who sponsored the Metropolitan Opera tour — which had reduced its scope due to high costs and would end in 1986 — launched their own opera company.

At the same time, NEA challenge and advancement grants helped both fledgling and existing opera companies make qualitative improvements to their productions and casting. And visionaries took the resources they found and ran with them. In Houston, newly flush with oil money, civic leaders, ambitious to put their city on the national map, backed the young David Gockley, who became the company’s general director in 1972. He promptly changed the company’s focus from star casts and standard repertory to young American singers and the creation of an American canon, and in less than a decade, built Houston Grand Opera into the country’s fifth-largest opera company. In 1987, HGO would open a grand new opera house.

Scorca calls the 1970s expansion “the powerful aftershock of the earthquake of the 1960s.” Seismic tremors, he says, continued into the 1980s, when 17 current OPERA America members were founded, including the last of the largest companies, LA Opera, launched in 1986. For nearly two decades, opera in Los Angeles had been supplied by an annual visit from the New York City Opera, but in the early 1980s, the opera-presenting board decided that it was time to create their own entity. Opera companies continued to grow in size. In 1980, 15 of OPERA America’s members had budgets greater than $1 million. In 1990, 45 did. And while the biggest companies still recruited famous European singers, the exponential growth in regional opera fueled the demand for American performers, who found they could make a respectable living traveling around the country, an alternative to the yearlong contract in a European house. Opera companies also realized that launching their own young artist training programs, as pioneered in San Francisco, Santa Fe and Houston, could help provide them with a steady supply of young talent.

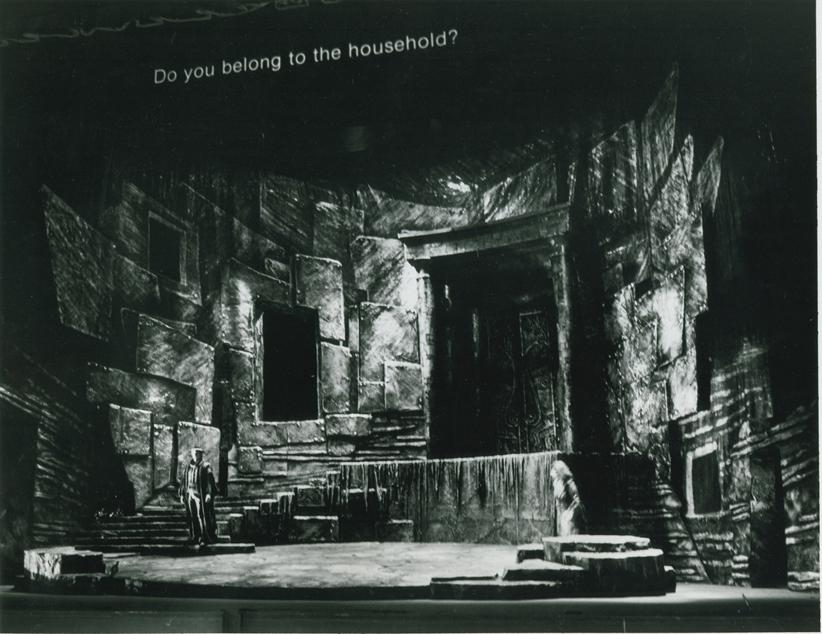

Even in the 1990s, when national audience surveys indicated that cultural participation was declining in some areas, opera continued to see growth. More new companies formed, most of them intentionally smaller operations. Some were located in areas that already had major producers, like Marin County’s Golden Gate Opera (1996); others were niche endeavors like the early-music Opera Lafayette (1995) and the new music incubator HERE (1993). The introduction of projected titles, pioneered at Canadian Opera Company and launched in the U.S. at the New York City Opera in 1983, had further galvanized the field. Titles were quickly adopted across the country, lowering the barrier to entry for audience members who no longer had to memorize the libretto before attending. Titles also helped to expand the repertory: It was now possible to follow the complicated plots of Handel operas and appreciate the works of Janáček and Dvořák, despite their less familiar Eastern European languages. Opera also got a boost from the international sensation of the Three Tenors, whose concert performance in Rome on the eve of the 1990 FIFA World Cup final reached a global audience. Suddenly, “Nessun dorma” was a hit tune, and for a decade, the trio’s concerts and recordings kept opera in the forefront of public consciousness.

After 2000, however, the world altered. The September 11, 2001, attacks had a profound effect on the cultural world, especially in New York City, where people abruptly stopped going out in the evening and hesitated to purchase tickets for future events. This change in activity, which might otherwise have been temporary, masked a more profound shift. The wiring of the country for high-speed connectivity, leading to the dot-com bubble and then its bursting in 2002, also meant that audiences who once relied on live theater and other cultural events for entertainment could now stay home and enjoy a wide range of excellent content for free in their own living rooms, with no transportation, babysitters or expensive tickets required. This new reality dramatically changed the landscape for cultural institutions that had long relied on subscription to fill their theaters.

This heightened competition for the attention and funds of the cultural attendee posed new challenges for opera companies accustomed to depending on a substantial core of loyal, frequent attendees. One of the most notable examples was Lyric Opera of Chicago, which had for years prided itself on selling out entirely on subscription. After 2002, that ceased to be the case. Like other opera companies, Lyric had to rethink its marketing operations and learn how to maximize sales of single tickets.

The Great Recession of 2008–2009 further shook the opera world, as financial instability translated into audience dropoff and philanthropy shortfalls. Four large opera companies, already in financial distress before the recession, shut down. The recession worsened matters at the New York City Opera, one of the country’s biggest and oldest groups, which had been in crisis for years, amplifying the effects of a series of disastrous choices that ultimately led to its bankruptcy in 2013. Others were better able to weather the changed environment by trimming budgets and seasons. For some, the change would not be temporary, and companies that continued to present fewer productions and performances would also continue to have smaller total audience numbers. Furthermore, with subscriptions no longer a given, individual audience members were attending less frequently. From 2000 to 2010, total attendance figures in OPERA America’s Annual Field Report showed that on average, opera companies saw a 28 percent drop in total attendance. For the largest companies, the average drop was 50 percent.

This change in audience patterns became part of yet another challenge. Even if companies were presenting fewer performances, their expenses were not proportionately smaller, as the primary cost driver of opera — the labor of its performing artists and stage workers — continued to rise. Ticket prices could increase somewhat, but not as much as costs. This was not a new phenomenon: The percentage of an opera company’s budget covered by ticket sales had been declining for decades. When the opera boom first began, box office receipts could be expected to pay for 50 or even 60 percent of an opera company’s operation. By 2010, that percentage, on average, was 27.7 percent, and continuing to decline.

Thus, an increasing percentage of the total had to come from philanthropy. Most of the critically important individual donors came from the audience: opera lovers who paid considerably over and above the ticket price to sustain the institution. As David Gockley, who went from Houston to run San Francisco Opera in 2006, noted at the time of his retirement in 2016: “The traditional audience, most of whom are subscribers, are being replaced by younger people who are more casual, less loyal attendees. Subscribers contribute; nonsubscribers do not contribute.” At the top level, new billionaires, who made their money in tech and finance, proved less interested in legacy cultural institutions than earlier generations of wealthy people, preferring to devote their philanthropy to world-changing initiatives like education or disease eradication. Opera companies had already seen a marked diminution in corporate support, as local entities, such as banks, were swallowed up by national enterprises that had different philanthropic priorities. And government funds devoted to the arts, whether local, regional or national, did not increase along with arts-organization budgets, and thus represented an ever-shrinking percentage of total philanthropy.

Yet despite the challenges posed by a radically altered environment, the last two decades have been marked by a new wave of opera-company creation: 40 current OPERA America members were founded between 2000 and the present. They are, for the most part, small. (Only Opera Parallèle, Opera Naples, Beth Morrison Projects and Opera San Antonio are OA Budget 3 companies, with annual budgets of $1,000,000– $3,000,000; the rest fall in the Budget 4 and 5 categories.) Many of them represent a new flowering of “indie opera,” which Scorca sees as a healthy reaction to the current world. “The training infrastructure of university and conservatory opera programs and young artist programs has grown tremendously, while the established infrastructure has shrunk since 2008, reducing productions and performances. So, there’s a big pipeline of training, and a smaller pipeline of hiring. But the barrier to entry is much diminished. In 1995, if you wanted to start an opera company, you had to have money to print marketing brochures and fundraising letters. Today, you can do it all on social media, websites, e-mail and crowdsourcing. Entrepreneurial artists are creating their own opportunities and fueling a second wave of development.”

These indie opera companies have altered the definition of what opera can be: There needn’t be an orchestra in the pit or flying scenery or even a theater. Companies like Heartbeat Opera have adapted classic works, rescoring them for small ensembles, rearranging and cutting them, and, in the case of Fidelio, using a filmed ensemble of real prisoners to sing the choruses and drive home the production’s contemporary message. The Industry performed Hopscotch, a new opera with multiple composers, in 24 limousines that drove around Los Angeles. The greatest talents honed in these kinds of enterprises, Scorca says, will find their way into the bigger companies, and shake them up, as well. “These companies may not be around for a 25th anniversary, but longevity is not the measure of their great contribution. Rather, it is their creativity, innovation and talent discovery.”

Older companies have also embarked on new artistic strategies in response to economic pressures. For some, cutting back on mainstage productions has created opportunities to perform different, often riskier repertoire in smaller, alternative spaces. Moving out of the opera house has increased geographic and audience reach. It has also helped fuel a boom in the creation of new repertoire, which has accelerated dramatically in the last decade, with operas tackling all manner of contemporary subjects, including hot-button topics like war, sexual identity and race. The resulting artistic and community vibrancy and diversity of these new endeavors, even if born of necessity, have helped invigorate the art form and its practitioners.

The expansion of opera beyond its traditional orthodoxies, spaces and audiences represents both a necessity and an opportunity for the future of opera in America. A major aspect of that expansion is work in civic practice: finding ways to make the opera company an essential part of the community in which it lives and to communicate its public value. Today, embracing that perspective may be a matter of survival. “Even if companies found some miraculous way to fill every house and increase every production by two performances, given the cost structure, earned income is still going to be a small share of overall income,” says Scorca. “And there aren’t enough opera-passionate people to support a lot of our opera companies. They need support from people who aren’t passionate about opera, but realize that ‘the opera company is doing great things for the community, and we’ve got to have it here.’”

Fifty years after OPERA America’s founding, its initial promise has been borne out by the sheer size and variety of the field. Of today’s 149 Professional Company Members, nearly 75 percent were founded in 1970 or later. Sixty-two Educational Producing Affiliate Members now present staged operas for enthusiastic audiences. Opera exists in major cities and tiny towns; it is a vacation destination and a tourist draw. Creative administrators and entrepreneurial artists are reinventing the art form and the institutions that present it. New creators have been welcomed, their talents changing and enriching the landscape.

And while innovations like streaming and HD transmissions have increased access to opera, as did public television with Live from the Met back in the 1970s, and the Met radio broadcasts in the 1930s, experiencing the art form live, in the theater, remains vital. “Going to the opera is more than just going to the opera,” Scorca says. “It is an act of civic convergence, where you come together with your neighbors, around something that is not politically charged or intrinsically divisive. I think people still crave that civic connection, and that convening around an inspiring, neutral stimulus. It happens in companies and in cities large and small all the time, and it has a value beyond opera alone.”

This article was published in the Fall 2019 issue of Opera America Magazine.

Heidi Waleson

Heidi Waleson is The Wall Street Journal’s opera critic and the author of Mad Scenes and Exit Arias: The Death of New York City Opera and the Future of Opera in America.