Revolutions in Tech

50 years of advances in technology and production

The stunning pace of technological development since 1970, the year of OPERA America’s founding, has radically altered the process of putting opera onstage and continually expanded the field’s range of production possibilities. In three primary areas especially — lighting, video projections, and sound — the changes have been so revolutionary that they would have been all but unimaginable 50 years ago.

The decade of the 1970s was a period of expansion of the role of lighting, as part of the increased emphasis being placed on opera’s dramatic values. “Lighting became more naturalistic and dynamic,” says lighting designer Rick Fisher. “The new theatricality demanded color and nuance to support the drama.” In the late 1970s and early 1980s, computer control boards started making their way into opera houses, their more elaborate cueing giving designers a tool to cultivate more sophisticated lighting plans.

The era saw much experimentation with individual light sources, as manufacturers worked to develop fixtures that emitted more light while giving off less heat. ETC’s Source Four fixtures and dimming systems, introduced in 1992, used innovative lamps, along with a reflector, to push more light forward while letting heat pass through the back. It was the beginning of a revolution in lighting sources, moving toward more versatile, powerful equipment.

The revolution continued with the rollout of LED lighting fixtures, starting in 2006. In their early years, these went through growing pains: consistency problems in color mixing and range, limited ability to blend with standard fixtures. But in the last decade, their role has matured. Their color-mixing capabilities provide a more responsive palette, and their compact profile allows installation in restricted spaces. Designer York Kennedy notes that LED fixtures are especially effective in bringing out accents in scenery architecture and in throwing even light onto cycloramas and drops. “The new LED fixtures are a great tool for the subtle and carefully timed gestures that opera demands,” Kennedy says.

LED technology has had a decisive impact on the rig for a production. One fixture — even one in a fixed position — can now do many things. If moving lights can be incorporated into the space and budget, they can expand possibilities for color, beam shape, patterns, and movement. The switch to LED isn’t easy: It means rethinking the infrastructure of opera-house lighting arrangements. The fixtures themselves carry onboard controllers for color, brightness and, in some cases, movement, relegating standard dimmer controlling to the past. “You need more data cable for control and less dimmer room capacity,” notes designer Duane Schuler. It also requires a new level of skill and training for lighting professionals, who must have a deep knowledge of computer controls and complex lighting-control computer networks.

In the past half-century, projection technology has become integrated into opera production in ways previously unimagined. All one needs to do is look back at recent examples such as The Dallas Opera’s Moby Dick and Everest, or Santa Fe Opera’s The (R)evolution of Steve Jobs and The Golden Cockerel. Washington National Opera’s recent mountings of Don Giovanni and Samson and Delilah both used the same modular set, but with projections to give the two shows very different looks. In cases like these, projected imagery has become an integral part of production design; indeed, another character within the piece.

The burgeoning use of projection stems from breakthroughs in the technology involved. Early projectors were bulky and noisy. It was difficult to place the equipment in a spot where it would be hidden and where the sound could be baffled, while still keeping the lamps cooled. Over the past decade, LED projection technology has changed all that. Current projectors are brighter and more compact. They are also quieter, which makes them easier to hang in locations closer to the audience, such as the front rail of the balcony: the optimum spot for front projections.

Video design used to be an analog process. In order for an image to be reworked, using the Pani and Pigi projectors prevalent from the 1970s to the early 2000s, film had to be perforated and spliced: a labor-intensive technique. “The reworking of an image often involved the use of complicated hand-cut masks and the reshooting of film,” says projection designer Elaine J. McCarthy. “You needed a three-day turnaround to see if the changes were correct. Each edit had to be carefully weighed in terms of the time available and the expense of the new slide.” Digital processes, McCarthy notes, have eased turnaround time, and correspondingly lessened the impact on the bottom line.

Powerful media servers, emerging in the early years of this century, allow for real-time previewing and simultaneous video editing. Designer Driscoll Otto notes that these servers allow production teams to build and preview their work in 3D before they ever enter the theater. This is an especially welcome development in light of the need to share limited rehearsal periods with other production personnel; if the projections are ill-prepared, it steals time from directors and other designers. “While a Broadway production typically has three to four weeks before opening, an opera may only have 10 to 15 hours onstage to coordinate the design elements with the cast and the music,” notes Rick Fisher.

“As the imagery moved from tape to the digital world, the creation of imagery has moved forward in leaps and bounds,” says designer Ben Pearcy. “Computers and software have allowed much more creativity in design, as well as a much faster response to production needs.”

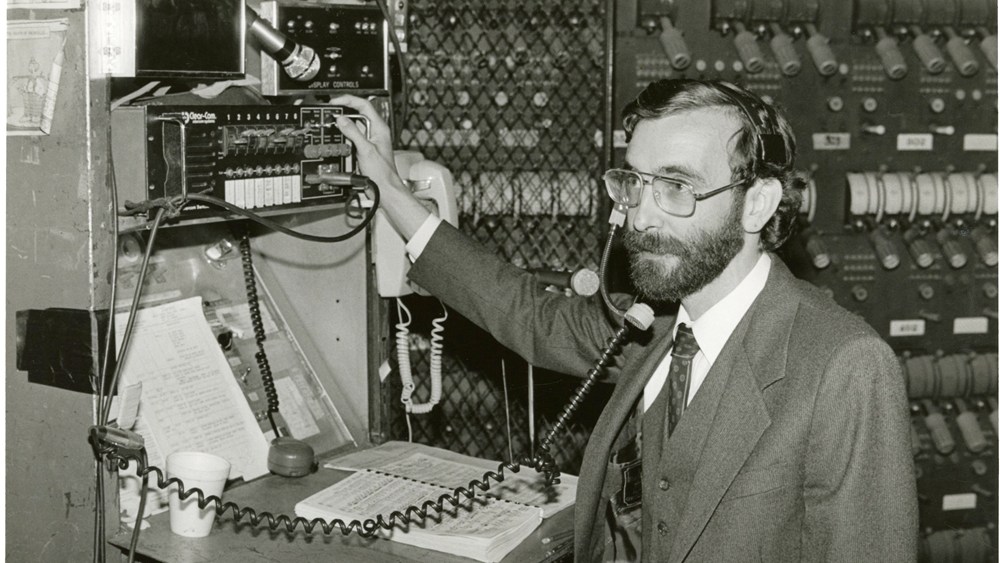

Once only discussed behind closed doors, audio amplification has become in some cases an overt element in opera performance. The modern era of miking in opera began with the 1987 premiere Nixon in China, in which John Adams called for amplification in his scoring. Since then, composers like Adams, David T. Little, and Mason Bates have written works with complex, layered orchestrations that demand voice enhancement. Meanwhile, opera is now being staged in sonically challenging venues: chamber works in black box theaters not designed for music; site-specific productions in spaces chosen for their dramatic appropriateness rather than their acoustic properties. Often, their acoustics demand technological intervention.

Technological advances have helped integrate amplification into the mainstream. Clunky, highly visible sound equipment is a thing of the past. Line array loudspeaker systems allow designers to sculpt sound coverage, balance frequency response, and send sound to all areas of the theater, so that the amplification truly augments natural voices rather than just making them louder. Wireless mics are easier to conceal than in the past — an especially important factor in the era of HD filming — and they’re also more reliable and responsive to the broad dynamics of the human voice, resulting in a more natural sound.

Today’s digital mixing consoles allow for efficient setups, and their recall abilities promote consistency from performance to performance. New digital processing equipment lets designers adjust sound system parameters from anywhere in the theater. “These systems help me quickly address the concerns of the performers, as well as any problems that might be audible to the audience,” says designer Kai Harada.

Karl Kern, Santa Fe Opera’s A/V director, notes that today’s programmable boards and speaker systems not only enhance the quality of performances, but also keep his budget under control: The process of moving systems in and out of repertory is much less labor-intensive than in the past. Moreover, as with lighting and video, today’s sound design tools allow for comprehensive preplanning and for previewing sounds without chewing up valuable staging time. “The equipment helps us meet deadlines and minimize errors in operation,” Kern says.

It isn’t just the instruments that have improved; sound designers now have a more sophisticated understanding of the art and science of amplification. “Savvy and sensitive designers have emerged who use their backgrounds in music, along with the new audio technologies, to build appropriate sound environments and enhance the audience experience,” says sound designer Mark Grey.

For all the innovations in sound, lighting, and projection, the technologies that have had the greatest impact on opera production are those that have transformed every aspect of our lives. Consider that in the 1970s, the fax machine represented the cutting edge in professional communication, allowing nearly immediate sharing of contract drafts, measurement charts, and show inventories. To relay information, technical directors put together fax trees, with each recipient forwarding the fax on to a number of others, with the hope that the messages would get through the complicated routing and result in answers.

In the age of the computer and the smartphone, faxing seems all but prehistoric. The internet has also made access to advice from other shops and vendors nationally and internationally much simpler. Videoconferencing lets design departments share imagery remotely. File-sharing platforms like Dropbox have streamlined the process of vetting materials and sharing inventories for co-productions and rentals. “It saves a lot of time over sending out slides and discs,” says Corinna Bakken, costume designer at Minnesota Opera. All of this represents a quantum leap in efficiency, as well as a significant cost savings compared to the days of long-distance bills and FedEx charges.

York Kennedy relates an instance when he had left a production, and last-minute changes to the show’s blocking necessitated a quick alteration of lighting cues. The theater was able to set up a Facetime stream that allowed him to watch the stage and then work with the programmer and stage manager to adjust the timings to the new staging. “Not ideal by any stretch, but we were able to make it work!” he says.

True, communication advances have not entirely eliminated the need for shipping or for direct, face-to-face contact, but projects can now move along at a much faster clip. Facebook costume groups and OPERA America’s listservs abet the process. “If we are looking for new construction techniques or specialty resources, the world is at our fingertips,” says Marsha LeBoeuf, costume designer at Washington National Opera.

Phones allow shoppers in the costume and props shops immediately to share images of potential purchases with designers. Another change in the costume-design process has been dictated by the market. Fabric stores have been cutting back on their stock; quite a few stores have disappeared altogether. Vendors that do custom fabric printing are to some extent filling in the gap, and current technology lets shops provide their own artwork. “This keeps costs down and gets us the imagery that the specific designs require,” says Daniele McCartan, costume director at San Francisco Opera.

From an audience standpoint, the most visible technological innovation of recent decades has been the introduction of supertitles, beginning with a Canadian Opera Company Elektra in 1983. In the years since, the creation and use of subtitles have evolved from a time-intensive process, involving making, editing, reprinting, and reordering stacks of projector slides, to an easy-to-manage system of digital projectors and software programs. In 1995, the Met introduced the first seat-back titles, followed soon after by Santa Fe Opera. Titles — both back-of-the-seat and overhead — have been responsible for bringing a new level of accessibility to the art form and arguably for expanding the audience for opera.

A technician is no longer somebody who carries a wrench or a hammer or a pair of scissors. Today’s production personnel need to have mastery of a vast toolkit of technological resources. Whether it is drafting a show for the scene shop, preparing a high-resolution image for printing a backdrop or run of fabric, or coordinating production elements during a tech rehearsal, they need a sophisticated understanding of computer technology. Fifty years ago, at the birth of OPERA America, this might have seemed pure science fiction. Now it’s a reality.

This article was published in the Fall 2020 issue of Opera America Magazine.

Paul Horpedahl

Paul Horpedahl was the productions and facilities director at Santa Fe Opera from 1998 to 2020.