From “Outreach” to “Civic Practice”

Fifty years of opera-company citizenship

Cincinnati Opera’s Opera Goes to Church concerts bring church choirs, opera singers and jazz musicians together in a place of worship. At press time, it remains unclear whether this year’s pair of concerts, scheduled for two different churches for 1,500 people apiece, will go forward as scheduled. But if they do — and if past years are an indicator — the tickets will be snapped up within hours . About 700 miles to the northwest, the Holland Fellows of Opera Omaha have been doing weekly creativity and songwriting workshops with the residents of a women-only homeless shelter and have recently begun a comparable project with young men in a correctional facility.

In 1970, the year of OPERA America’s founding, opera companies’ connections to their communities consisted mostly of school education programs. Later, the field expanded its ventures outside the opera house under the rubric of “outreach” or “community engagement,” while still positioning such efforts as ancillary to mainstage productions. In recent years, however, projects like Omaha’s Holland Community Opera Fellowship have been launched with a different objective. These initiatives operate in partnership with community groups, offering the resources of the opera company for projects that further the goals of those groups. They are not about marketing or audience development for opera performances, but about demonstrating the company’s commitment to being a good community citizen. In this formulation, the opera company is about much more than putting on performances.

The terminology has changed to reflect that shift, with “civic practice” as a more representative and less patronizing heading for the work. For Marc Scorca, president/CEO of OPERA America, the word “outreach” implies that other people “live in deserts that need to be filled with opera. But people have their own rich cultures; no one needs opera to be ‘cultured.’ ‘Engagement’ sounds like ‘I want you to be engaged in what I am doing.’ There’s no reciprocity.” “Civic practice,” by contrast, denotes work in progress, with collaborative relationships that strengthen over time.

“We have had to get off our pedestal and stop conveying the message, ‘We know what’s best for you.’” says Charles MacKay, former general director of Opera Theatre of Saint Louis and the Santa Fe Opera.

Fifty years ago, the most visible community involvement for most companies consisted primarily of “student matinees,” in which school kids were bussed in for dress rehearsals. “It was the easiest thing to do — a product that was already in place,” says Stuart Holt, the Metropolitan Opera Guild’s director of school programs and community engagement. The Santa Fe Opera had “youth nights” practically from its founding. But when MacKay started as an administrative assistant in the early 70s, the organization did not even have a separate education department. The sales manager handled the student program: an indication that the company viewed such activities primarily through the prism of audience building. Even when opera education programs went out into schools, they generally focused on telling an opera’s story and providing musical excerpts, with the aim of preparing students for a performance at the opera house.

The scope of education projects began to broaden in the 1980s and 1990s, with initiatives like the Metropolitan Opera Guild’s school program of opera creation by students and OPERA America’s curriculum, “Music! Words! Opera!” These newer curricula had broader aims: cultivating student creativity and helping classroom teachers use opera to teach literature, history and other subjects, with study goals linked to academic performance standards. Teacher training and professional teaching artists were also key aspects of the program. Allison Felter, who oversees education and community programs at Opera Theatre of Saint Louis, where M!W!O! was piloted in 1990, says, “It was wildly successful and popular. Partnering with an outside professional institution gave music teachers a lot of credibility in the schools.”

Scorca says, “I liken our Music! Words! Opera! series to Martin Luther and the 95 theses. It created a revolution. Long-term partnerships became the norm. For opera companies, it expanded their understanding — the child was the beneficiary, not the opera company. Some of the students may become opera lovers, but the immediate goal is improving student learning.”

In the years since, education has remained an important element tying companies to their communities. But the concept of civic practice has also taken hold, and with it, the idea of working in long-term partnerships to advance the work of other community groups. This kind of endeavor takes opera companies out of their bubble — and often, their comfort zone. Services and resources are offered without any preconceptions about what the partnership or the final product, if there is one, will look like. In the past five years, with the aid of grants from the NEA, OPERA America has hosted a series of workshops to help guide opera companies embarking on this new way of working. Sessions have stressed the importance of showing up, being “a good guest,” listening to the needs and goals of others, and, critically, relinquishing control.

When Anthony Freud came to Lyric Opera of Chicago in 2011, one of his first initiatives was the creation of Lyric Unlimited, an entity designed to operate outside the mainstage season and to be a nimble arm of the organization that could be responsive to community needs and interests. Cayenne Harris became Lyric Unlimited’s first leader in 2012. “Lyric Unlimited is not a marketing initiative, to get people to buy tickets,” she says. “The idea is to think about how opera can resonate more meaningfully with people who don’t have a connection to the art form.”

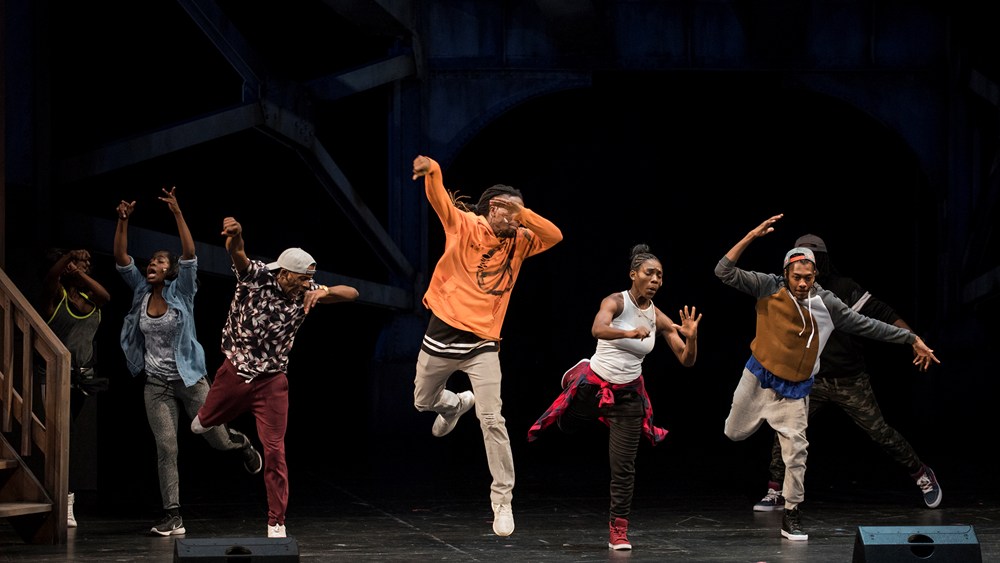

For Harris, one of Lyric Unlimited’s most impactful projects was pioneering a way “to work directly with communities to co-create, to move away from the old model of presenting a finished model to an audience.” Its first foray in that area, Chicago Voices, was a multiyear project that involved six different groups, including a theater troupe of disabled actors, a Serbo-Croatian band and an ensemble of young African Americans. “It required Lyric as a company to work in ways it never had before — a humbling process — and to broaden the definition of opera,” Harris says. “We got on a different channel to see how we could share resources — expertise, lighting, sets, putting together production teams — in service of a community interest. Our job was to support what these groups wanted to say, working directly with them to realize the vision they had for their artistic product.” The result was satisfying for all concerned: The shows had sold-out houses, filled with people who came to support their loved ones and got excited about the other groups on the program, as well. This practice has continued in a new partnership with the Chicago Urban League, a project called Empower Youth. “There are people who had no connection to Lyric Opera of Chicago, or to opera at all, who now feel a deep connection,” Harris says.

Civic practice takes different forms in different places. In 2006, Cincinnati Opera’s director of community relations, Tracy L. Wilson, persuaded the pastor at Allen Temple AME in Cincinnati to put on a collaborative concert, which she saw as a spiritual community connector. No one knew what to expect. “We thought success would be 300 to 400 people in a church that holds 1,500,” she recalls. “Just before it started, I turned around, and it was standing room only.” The project has forged some unexpected community connections. Church choirs have sung together and gotten to know each other; church members show up at Opera Goes to Temple, which has a very different liturgical vibe; and the opera singers have become familiar figures in town. Bass Morris Robinson, a frequent participant who sometimes accompanies the choir on drums, sang Porgy in Cincinnati’s Porgy and Bess last summer. Wilson says, “I was in the top balcony in Music Hall, and in the middle of the performance, someone yelled, ‘Isn’t that the dude that plays the drum set at Allen Temple?’”

Some opera companies have already found that a commitment to civic practice is the key to their survival. When Ned Canty arrived as general director of Opera Memphis in 2011, the company was in financial peril, going through what he calls “a crisis of relevance” in a city where the recession was still in force. The company had engaged in some community work but, as elsewhere, its role was peripheral. Canty launched a variety of projects, including 30 Days of Opera, which stages pop-up events around the city. Other initiatives included commissions of pieces set in Memphis and collaborations with the nearby military base.

“As we went forward, finding the ways in which we could do good using tools and resources we already had, it became clear how much low-hanging fruit there was,” Canty says. “It took a lot of cold-calling — a small social service agency, a civil justice organization — to find the right partnerships.” Next season’s mainstage La bohème is actually the result of conversations about race and opera with partners in Opera Memphis’ civic practice work: It will be set on Beale Street in the 1920s and have an all-black cast. Canty will co-direct it with Dennis Whitehead Darling, a recipient of one of the company’s McCleave Fellowships, which create early-career opportunities for directors and conductors of color.

Today, Canty says, “our civic practice work has become the public brand of the company. More people know us through that.” The rebranding was life-saving: An influx of new money for civic practice work kept the company afloat from 2012 to 2015, and the rethinking of its mission has been an ongoing attraction for philanthropists who might otherwise not be interested in the opera company.

Opera Theatre of Saint Louis pioneered work in civic practice with its efforts to engage faith leaders in advance of its production of John Adams’ controversial The Death of Klinghoffer in 2011. The resulting community partnerships, and the company’s standing Engagement and Inclusion Task Force, have become key parts of its operation, and avenues for OTSL to serve as a convener around difficult issues.

For Opera Omaha, the Holland Community Opera Fellowship, now in its third year, is central to the company’s transition from a purveyor of mainstage operas to a cultural resource for the community. Two full-time Holland Fellows, singers chosen for their entrepreneurial, social and emotional skills, serve two-year terms and are tasked with initiating, building and sustaining community partnerships and executing the collaboratively devised programs. In the spring of 2020, the fellowship had 40 partnerships, about 20 of which had active program work. A 12-member community panel guides and steers the fellowship, helping, among other things, to identify priority community needs.

At one point, the community panel identified homelessness as a key civic problem. “We worked forward from there,” says Lauren Medici, Opera Omaha’s director of engagement programs. “We won’t solve that problem, but we can be a resource for organizations that are doing good work in that space.” The creativity and songwriting workshops with two homeless shelters, for example, came out of those discussions. In the first two years of the Holland Fellowship program, 18,000 people participated — double the number that the company reached before the program was launched.

Most of the Holland Fellowship programs are about process, not product, and their success, Medici says, is measured not by applause, reviews or ticket sales, but by metrics like, “Was there a sense of joy and excitement in the room? What reflections did the participants share?” At a workshop that the fellows ran for the healthcare staff at the women’s shelter, participants talked about the pleasure of doing something creative for an hour, outside the stress of their jobs, and how they wanted to replicate it for others. The partnerships at the homeless shelters have developed to the extent that the residents and staff, initially dubious about opera’s relevance to their lives, asked if they could attend a mainstage performance, and 25 of them attended a Sunday matinee of Abduction from the Seraglio.

Today, civic practice can take many forms, but fundamentally, it involves rethinking what it means to be part of a community. Scorca envisions scenarios where opera companies consult with their community partners before making final decisions about mainstage repertoire. “Why not ask a few women’s shelters in the city if they would be willing to work with us around a production of Don Giovanni before deciding to do the opera — instead of doing it three months before the performances?” he says. No matter what form civic practice takes, Scorca says, it is now essential. “Every corporation thinks about social responsibility, and opera companies are multi-million dollar corporations,” he notes. “They need to be seen to be of value to communities beyond just putting on beautiful performances. An opera company has to be seen as central, not ancillary, to a healthy community.”

This article was published in the Spring 2020 issue of Opera America Magazine.

Heidi Waleson

Heidi Waleson is The Wall Street Journal’s opera critic and the author of Mad Scenes and Exit Arias: The Death of New York City Opera and the Future of Opera in America.