The 90s: Culture Wars

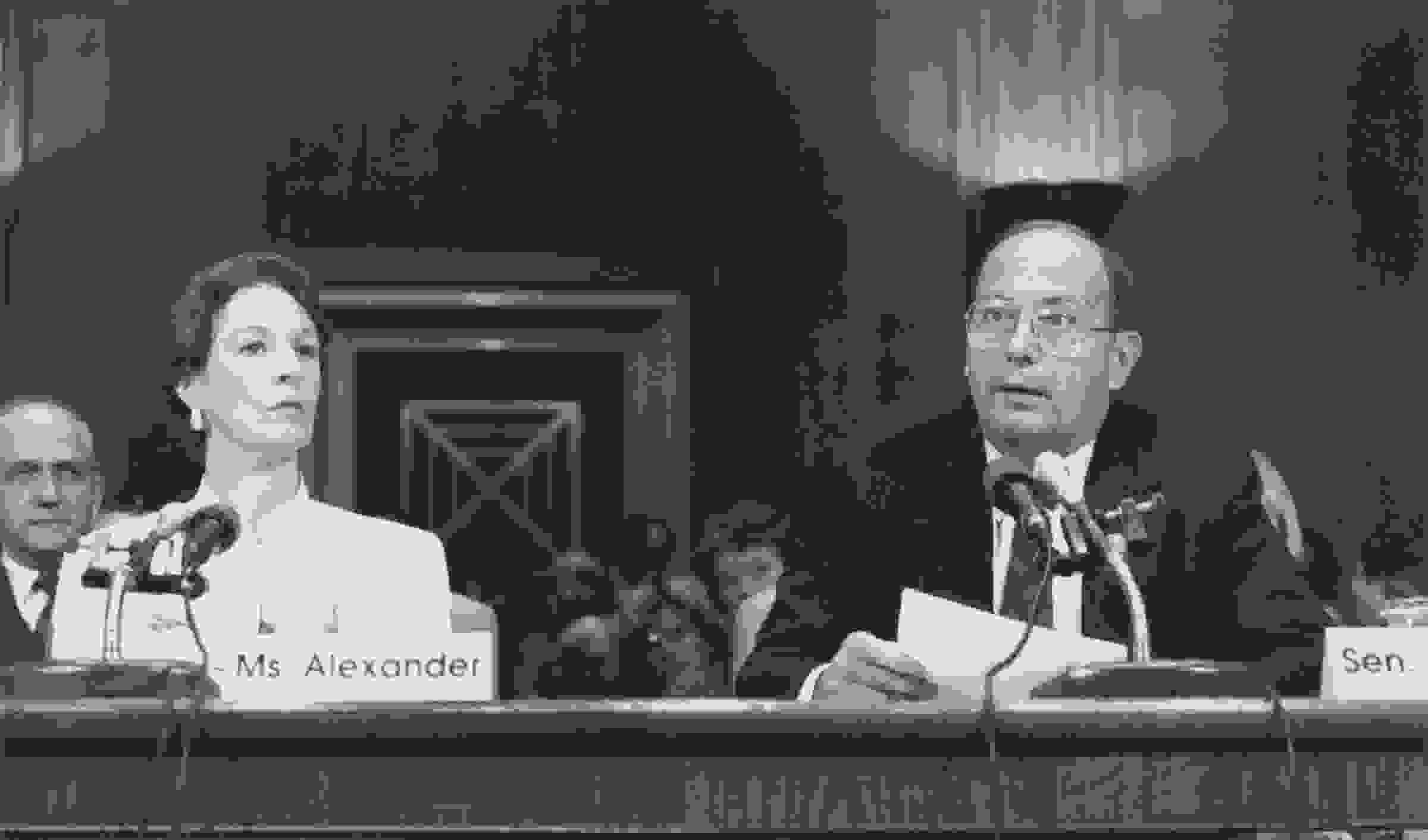

The National Endowment for the Arts, established in 1965 as one of Lyndon B. Johnson’s Great society programs, has through much of its history ended up in the center of political crossfire. But its existence was never more threatened than in the 1990s. The controversy started in 1989, set off by exhibits of the works of two photographers that included Andres Serrano’s Piss Christ and Robert Mapplethorpe’s homoerotic photos, both of which received NEA funding. Conservative politicians railed against the perceived sacrilege and obscenity of the works, and painted the agency as a betrayer of American values. In the years following, measures to defund the NEA entirely made their way through Congress.

The battle itself did not directly affect opera: No operatic offerings came under political fire. But it did have a significant impact on the workings of the NEA, which since its founding had helped seed the field’s burgeoning growth. In the first quarter-century of the NEA’s existence, national audiences for opera had risen from three to 18 million, in no small part due to the agency’s efforts. The threat to the NEA was unquestionably a threat to American opera.

The agency survived the “culture wars,” but its fiscal year 1996 budget was slashed from $162 million to $99 million. Nonetheless, the NEA remained the nation’s single largest financial supporter of the arts. Meanwhile, in response to the controversy, the agency changed its method of operation and the structure of its grants. Six members of Congress were added to the National Council on the Arts to contribute to the agency’s governance. The percentage of agency funds that went directly to states rose from 35 to 40 percent. Grants would no longer be allotted to individual artists, nor would grant money be distributed to arts organizations for operating expenses. Instead, NEA grants are now awarded on a project-by-project basis.

Despite continued threats to the agency’s existence in 2017, 2018, and 2019, when the White House budget eliminated funding for the NEA (as well as for the NEA, IMLS, and the Corporation for Public Broadcasting), Congress has continued to support the NEA, and its total budget has now risen back to its 1995 level, before adjusting for inflation. In fiscal year 2019, it distributed $2 million in direct grants to opera projects; state arts councils also supported opera through their share of the agency’s budget. Aside from the direct value of the funds themselves, an NEA grant can serve as the ultimate sign of merit, attracting private donations and enhancing an organization’s public image. Fifty-five years after its founding, the NEA remains a vital contributor to the field of opera.

This article was published in the Spring 2020 issue of Opera America Magazine.