Pittsburgh models artistic collaboration and downtown revitalization

The beating heart of Pittsburgh lies at the confluence of the city’s three rivers, where the Allegheny and Monongahela rivers combine to become the mighty Ohio. There, on a point of land that juts into the water, lies an exquisite state park, where musicians of all ilks gather to put on outdoor concerts in the summers with the Steel City’s famous fountain and skyline as backdrops. From that park, if you walk due east, past the towering glass spires of PPG Place and the bustling Market Square, you’ll encounter the Cultural District, the city’s arts haven, where operas, symphonies, ballets, and plays are constantly lighting up stages and marquees. Then, if you continue walking northeast for about a mile along Liberty Avenue, one of the city’s main drags, you’d arrive at a factory.

Now, a factory in Pittsburgh isn’t unusual. Pittsburgh was once one of this country’s industrial capitals. But this isn’t a typical factory; this factory produces opera. The Bitz Opera Factory, formerly a 19th-century air brake factory and now a LEED Silver-certified building, is the home of Pittsburgh Opera, founded in 1939 by a quintet of femme fatales. That company, the city’s largest producer of opera, is just one of the cogs in the city’s cultural machinery alongside the symphony, opera, ballet, and other major institutions, all of which have earned national recognition for the quality of their performances. This is thanks in part to the larger-than-average philanthropic largess left over from the city’s manufacturing peak. Even though Pittsburgh has shrunk to become a medium-sized city — the metro area’s population is about 2.4 million people — a 2020 report by the Greater Pittsburgh Arts Council ranked Pittsburgh first of 10 benchmark cities like Baltimore, Cleveland, and San Diego in terms of foundation contributions.

The city’s arts organizations don’t view each other as competitors for those philanthropic dollars, however. On the contrary, they’ve forged a stronger, more unified arts ecosystem by working together and building lasting partnerships. “I’ve lived in San Francisco and Los Angeles and other major cities, and believe you me, this sort of collaborative spirit is rare,” says Pittsburgh Opera’s general director, Christopher Hahn. Professionals from these organizations gather together in regular meetings to strategize about tackling the challenges of the 21st century, including the task of drawing residents back to Downtown. Like many other metro areas, Pittsburgh is struggling with a hollowed-out core due to remote work, an increasing homeless population, and a perception of decreasing safety. “The pandemic was devastating,” says Janet Sarbaugh, former vice president of creativity at the Heinz Endowments. “But I’m optimistic that Pittsburgh can bring the Downtown back again with the arts playing the key role.”

ASSEMBLY LINE

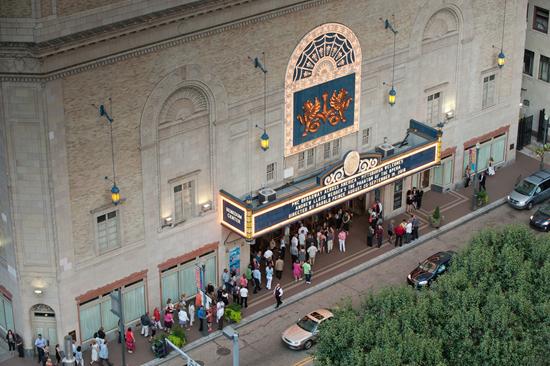

This won’t be the first time the arts will have transformed Downtown. In 1984, Henry John “Jack” Heinz II, the CEO of the H. J. Heinz Company — never eat Hunt’s ketchup in Pittsburgh — founded the Pittsburgh Cultural Trust as an economic development engine that would use the arts to clean up the Downtown area. The Trust has since grown to become the fourth largest performing arts conglomerate in the U.S. and Canada, with a $64 million budget. “I’ve been around long enough I’m like furniture here,” says a chuckling Rona Nesbit, executive vice president at the Pittsburgh Cultural Trust, recalling how the 14-block area the Trust now owns used to host a variety of sex shops and pornographic bookstores and movie theaters. “People would drive into town to go see the opera, park, and run in as fast as they could,” she says. “Then they’d run back out, just hoping that their cars were still there.”

The Trust began snapping up theaters and properties, restoring venues like the Benedum Center, where the opera now performs, and working with the city to oust the seedier shops and welcome a variety of hotels, restaurants, and retail options. Soon, companies like the opera and the ballet and some of the theaters would enter into partnerships with the Trust to become “resident companies” that regularly rented the renovated theaters. “Meanwhile,” Nesbit says, “the Trust’s intention is to program around its partners’ offerings — to present attractions that Pittsburghers otherwise wouldn’t get to experience.”

Even though the Trust came to own most of the performance spaces, there was a time when there were six different box offices dotted around Downtown, which rubbed some leaders as wasteful. “Two arts company board chairs came to the foundation community and said ‘this is crazy!’” Sarbaugh says. In the 1990s, a group of the city’s largest organizations, including the opera, joined together to form the backbone of the city’s cultural landscape: the Shared Services program. That program, administered by the Cultural Trust, was intended to help arts organizations firm up the administrative ends of their organizations without compromising their productions, concerts, and shows. “That’s really key. This does not homogenize the artistic product,” Nesbit says. The Heinz Endowments provided funding for the first three years of Shared Services, and now, a $1 fee on every ticket sold in the Cultural District helps to fund various aspects of the program, like a human resources consulting company, district-wide research projects, and printing costs for joint promotional activities.

“It sounds boring and bureaucratic, but the ability to offer really good health insurance is crucial to staff retention,” says Hahn. “The economy of scale also helps with the little things like toilet paper and ink.” The program helps reduce costs for ticketing services and administrative health insurance for the member organizations, which now include Pittsburgh Opera, the Pittsburgh Cultural Trust, the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra, Pittsburgh Ballet Theatre, the August Wilson Center, the Pittsburgh Public Theater, and the Pittsburgh CLO.

MACHINE COGS

The collaborative spirit behind Shared Services extends beyond the city’s largest arts groups to those outside of the program, as well. There’s Pittsburgh Festival Opera, whose artistic director — the decorated mezzo-soprano Marianne Cornetti — regularly appears on the Pittsburgh Opera stage, as well as the multi-modal company Resonance Works. Pittsburgh Opera is also acting as a fiscal sponsor and providing grant-writing assistance to the historic National Opera House, where singer Mary Cardwell Dawson headquartered this country’s first Black opera company.

“Everything is just so completely interconnected here,” says Jonathan Bailey Holland, the recently appointed head of the School of Music at Carnegie Mellon University, a school world-renowned for its arts, administration, and technology programs. Pittsburgh Opera has partnered in the past with students to create short new operas and to code an augmented reality app for opera attendees, and graduates from the school’s arts administration master’s program have gone on to staff top opera companies around the country. The opera’s artists have also appeared often on Pittsburgh Ballet Theatre’s roving mobile stage and with dancers from Attack Theatre and the city’s early music organization Chatham Baroque.

While schools and these smaller organizations don’t directly benefit from the Shared Services program, whenever they put on a production at a Trust-owned venue they have access to the Trust’s ticketing service, which has collected decades’ worth of data. (The Pittsburgh Cultural Trust is now the largest multi-organization Tessitura Network user group in the world.) That data has proved an invaluable resource over the years in tracking audience behaviors.

Leaders in other cities like Richmond, Virginia, Greenville, South Carolina, and many others have had meetings with the Trust to explore ways to begin building a Shared Services-like consortium, but “it’s difficult to find the historic level of philanthropy in Pittsburgh that’s fueled so much of the growth,” Sarbaugh says. Plus, the benefits aren’t evenly distributed among participating organizations. “The Trust sells about 50% of the tickets in the district,” Nesbit says. “Do we reap 50% of the benefits from Shared Services? No,” she continues. “But this is our mission: to help curate, and support an entire cultural district. But when we talk to other cities about Shared Services, that imbalance is where it sometimes falls apart.” Still, looking to the future, pursuing this cooperative “stronger together” model might be arts organizations’ best chance for success.

PRODUCTION LINE

Marianne Cornetti in Pittsburgh Opera’s 2022 Rusalka

Marianne Cornetti in Pittsburgh Opera’s 2022 Rusalka

In Pittsburgh’s opera scene, there’s something of a manufacturing line from local schools to the residency program to the professional stage. Mezzo-soprano Marianne Cornetti is living proof. A Pittsburgh native, she was one of Pittsburgh Opera’s very first resident artists in 1990. (Since Cornetti launched her career, Pittsburgh Opera’s two-year Resident Artist program has graduated scores of singers and helped launch them to careers singing on the world’s top stages.)

After her residency, Cornetti became a “planned artist” at the Metropolitan Opera, singing in various non-starring roles. After several years, she thanked the company and set out on her own, auditioning for larger roles. “The company manager at the time told me, ‘I think you’ll be back,’” Cornetti recalls, chuckling. “And then, I said, ‘I hope through a different door!’ And four years later, I did just that, singing as Amneris in Aida.”

In recent years, Cornetti’s Pittsburgh connection has come full circle. She now teaches at Carnegie Mellon University and took over Pittsburgh Festival Opera in 2019. That company, like Pittsburgh itself, is continuing to reinvent itself in a changing economy, in part by placing a higher emphasis on its educational offerings.

RADICAL CONNECTIONS

Shared Services isn’t the only cost-saving collaboration among city arts organizations. Pittsburgh is also home to the Allegheny Regional Asset District (RAD), which since the 1990s has distributed half of all proceeds from a 1% sales tax in Allegheny County to the county’s libraries, parks, public transit, civic and arts organizations, and sports facilities. In 2022, RAD distributed about $127 million in grants, about 12% of which went to arts organizations. It’s one of the other significant players in the funding scene aside from foundations, and, like the foundations, RAD has been encouraging collaboration among the city’s arts organizations to consolidate resources.

RAD has a dedicated Connection Grant designed to incentivize organizations to share costs, whether that’s for a shared administrative position or office space. Pittsburgh Opera, for example, hosts several other arts organizations at its factory headquarters space. Some of these organizations received money from RAD for build-out costs to kickstart that partnership.

“There are some truly fascinating models for shared services, like the financial cohort of the Kelly Strayhorn Theater, the Union Project, the Pittsburgh Glass Center, and the New Hazlett Theater, all sharing a single chief financial officer,” says Heinz Foundation consultant Janet Sarbaugh, explaining that alone, no one of those organizations could afford a CFO. “Looking ahead, human resources has been a real issue for a lot of performing arts organizations — this could be the next area for a shared services program,” she adds.

This article was published in the Spring 2023 issue of Opera America Magazine.

Jeremy Reynolds

Jeremy Reynolds is the editor of Opera America Magazine, and he also writes about classical music for Opera Magazine, the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Symphony Magazine, and The New York Times.