Voices Raised

Racially themed works bring new perspectives to opera’s stages

The problem isn’t that black people don’t like opera — the problem is that black people haven’t had their stories told in opera,” says playwright and librettist Marc Bamuthi Joseph. “How many times can I see Porgy and Bess?”

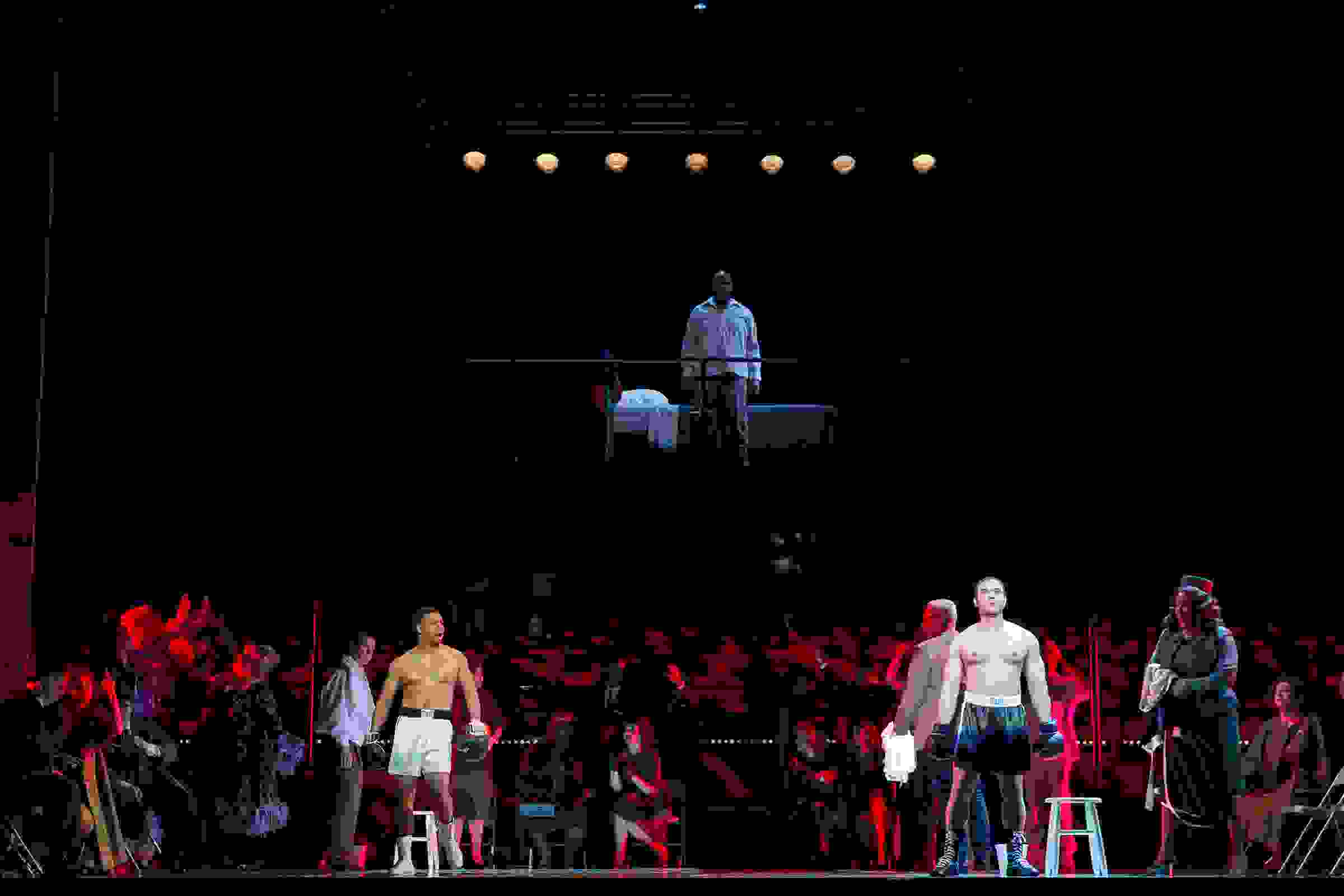

As if in answer to that question, a number of recent and upcoming American operas take a sharp look at the African-American experience. Joseph’s own We Shall Not Be Moved, with music by Daniel Bernard Roumain, premieres at Opera Philadelphia this fall; the work focuses on five Philadelphia teens who take refuge in an abandoned house with a tragic civil rights past. Terence Blanchard and Michael Cristofer’s Champion, presenting the life of boxer Emile Griffith as he battles the twin scourges of racism and homophobia, has proved to be among the most enduring of recent operas, with two important productions since its 2013 Opera Theatre of Saint Louis premiere, most recently at Washington National Opera. Frances Pollock’s Stinney: An American Execution, which bowed in 2015 at Baltimore’s 2640 Space, chronicles the true story of a 14-year-old African-American boy who was railroaded into a murder conviction and executed in South Carolina in 1944.

These works are notable not only for their focus on black characters, but also for their use of opera as a means of grappling with pressing social issues. Although the art form is often seen as apolitical, political engagement is in fact a thread running through much of opera’s history. “In Marriage of Figaro,” Frances Pollock notes, “Mozart is addressing issues of class and power.”

“From the Greeks to Shakespeare and Tony Kushner, theater has been a place where you can take large moral stances and defend them,” says librettist David Cote, who collaborated with composer Nkeiru Okoye on Invitation to a Die-In, about police shootings in African-American communities. “I love creating drama by putting a range of conflicting viewpoints on stage. Let them fight it out: That’s polyphony. That’s music.” Cote and Okoye’s performance art piece, which had its premiere this January in performances by the Mount Holyoke Symphony Orchestra, reaches its shocking conclusion with a coup de théâtre inspired by the finale of Poulenc’s Dialogues des Carmélites: “We thought it would be effective if the band itself were gunned down, one by one,” Cote explains. “Each instrument, each voice, drops out as the piece winds down.”

Some audience members complained about Invitation to a Die-In’s harsh ending. But composer Ted Hearne argues that the niche status of classical music makes it a relatively safe arena for bold political statements. “I can explore ideas that are provocative for an audience, and I can do that without worrying too much about selling tickets,” he says. “It’s not about going platinum.” Hearne is developing the oratorio Place — “part memoir, part flash documentary” — examining the intersection of location, history and personality in inner-city Chicago, collaborating on the libretto with poet and musician Saul Williams.

Marc Bamuthi Joseph sees the new breed of racially themed operas as a way for companies to move past the standard repertory and address the issues of our own time. “We should update our ideas of greatness and brilliance,” he says, “and expand our understanding of what’s beautiful to encompass the people standing beside us.”

Composers and librettists are of course primarily artists, not activists, and their attraction to racially themed subject matter tends to balance aesthetics with politics. “I don’t know if any artists deal with any issue because they think it will gain attention,” says Hearne.

“I was always concerned with social justice and race, but I was interested in the story,” says composer Daniel Sonenberg about his opera The Summer King. Chronicling the life of the Negro leagues catcher Josh Gibson, the work had its Pittsburgh Opera premiere this April.

“I chose [Champion] because it moved me,” Terence Blanchard says. “It moved me in a way that was tiring. The issues I’m talking about are universal. I’ve never thought of music as belonging to one race or people. To me, a C major chord vibrates the same way whether I’m playing it or whether a white person is playing it.”

Marc Bamuthi Joseph wrote We Shall Not Be Moved as a statement about education. The work stems from Joseph’s involvement with Opera Philadelphia’s Hip H’opera, a collaboration with Art Sanctuary that combines classical music with hip-hop to engage young people. The poetry that the participants wrote, Joseph noticed, suffered from a lack of greater perspective. “It felt like the kids were acutely aware of what was happening on their blocks but not what was happening in their world,” Joseph says. “I was struck by what that meant for the city’s near future. So the libretto sought to deal with marginalization within the public school system, intersecting with headlines of violence and injustice.”

Nkeiru Okoye tackled one of the great icons of African-American history when she wrote her 2014 Harriet Tubman: When I Crossed that Line to Freedom. But her Do No Harm, now in development, is concerned as much with the politics of gender as race. The opera, with a libretto by David Cote, tells the harrowing tale of a woman who suffers a stroke that leaves her speaking and walking with difficulty. Hospital doctors misdiagnose her condition and incarcerate her in a psych ward for seven days. Okoye is using the story to upend the operatic trope of female madness (think Lucia di Lammermoor, Anna Bolena, Elvira in I Puritani¸ Ophélie in Hamlet). “Most of these stories [in opera] about women descending into madness — they are being told by men,” she says.

Okoye is accustomed to dealing with the “feminist” label. Her 2016 comic opera We’ve Got Our Eye on You, a retelling of the Greek myth of the Graeae, features four women and only one man. “People call it feminist,” Okoye says, “But I’m female — what else am I going to write about? It’s not really a feminist opera. It’s simply about women.”

One dividend of racially themed works is that they create a stock of roles specifically tailored to black singers. “One of the biggest compliments I ever got was from a young black artist playing Emile in a workshop for Champion,” Terence Blanchard says. “He sang [the aria] ‘What makes a man’ and said, ‘This is going to be my audition piece for the rest of my life.’”

In mounting these pieces, producers often hope the diversity on stage will engender a new level of diversity in their audiences. “Any subject matter that enables [companies] to broaden their audience is appealing,” Sonenberg says about The Summer King. In preparation for the opera’s premiere, Pittsburgh Opera held community events in neighborhoods that may not contain many seasoned operagoers, but that have a historical connection to Gibson, who made Pittsburgh his home.

But it is not necessarily an easy task to engage black audiences. At Opera Conference 2017 this May, attendees were startled to hear the words of Keryl McCord, founder and CEO of Equity Quotient, an organization dedicated to bringing diversity and inclusion to nonprofit institutions. “I’ve gone three times,” McCord said about her opera-going experience, “and I’ve never felt more uncomfortable, because I didn’t see anyone in those spaces that looked like me.”

“When you speak about opera, diverse means 10-to-20 percent non- whites in the audience,” says mezzo-soprano Tia Price, who sang the role of George Stinney’s mother, Alma, at Stinney’s premiere, and also co-wrote the work’s libretto. “I think we will be stuck with a mostly white audience. There’s not a good way to get around that.” Op- era Philadelphia’s 2015 premiere of Charlie Parker’s Yardbird, the Daniel Schnyder/Bridgette A. Wimberly opera about the great black saxophonist, bears out Price’s assertion: A survey showed that 13 percent of single-ticket buyers were African-American — a definite uptick from the figures for the company’s other repertory, but still far from reflective of Philadelphia’s demographics.

Opera Theatre of Saint Louis had a somewhat different story to tell with its Champion premiere. Although the company did not do a formal audience demographic study, the work definitely attracted people who ordinarily don’t go to the opera: 43 percent of single- ticket buyers were newcomers to OTSL. And when Champion was staged in Washington, NPR’s Tom Huizenga wrote: “In 21 seasons of attending WNO performances, I’ve never witnessed a more diverse crowd.”

Explaining his opera’s appeal to black audiences, composer Blanchard says, “People want to see themselves.”

No matter how slowly these works change audience demographics, black artists nonetheless see them as a welcome development. “Working on Stinney was a way to bring my community into my work,” says Price. “I wanted my grandma to feel welcome.”

Quite a few of the creators of these works — Ted Hearne, Frances Pollock, David Cote, Michael Cristofer — are white, a circumstance that inevitably summons the term “cultural appropriation.” Daniel Sonenberg is white; so is Daniel Nester, who co-wrote The Summer King’s libretto, and Mark Campbell, who provided additional lyrics. But Sonenberg still feels the subject matter was fair game. “We have to be careful not to situate the story of Josh Gibson as exclusively about race or black history,” he says. “He’s an American hero. His story is about triumph over adversity. This is part of our shared history.”

Marc Bamuthi Joseph argues that color-blindness can go only so far. “I don’t think a white director is incapable of directing A Raisin in the Sun,” he says. “Are they best equipped, based on personal experience? Could David Mamet have written Fences? I don’t know. Opera companies have to have honest conversations amongst themselves.”

Cognizant of the perils of taking on Stinney, Frances Pollock drew members of George Stinney’s family into the process. “I met George Stinney’s cousin and I can’t describe how grateful she was to Frances for helping to tell this story,” says Tia Price. “We’re both going to the family reunion this year.”

All told, these operas can’t help but bring a measure of diversity to a field sorely in need of it. “This story won’t change the world,” Price says about Stinney, “but a community has been created as a result of this. To put this work on the operatic stage and start conversations — that might change things.”

This article was published in the Summer 2017 issue of Opera America Magazine.

Celeste Headlee

Celeste Headlee is the host of On Second Thought at Georgia Public Broadcasting and the author of We Need to Talk: How to Have Conversations That Matter.