Boundary Shift

Is it opera? Music theater? Or something else entirely? For innovative creators, directors and producers, the definitions may not matter.

The definition of opera has been in flux ever since Philip Glass wrote Einstein on the Beach in 1976, after which the director of the Netherlands Opera, commissioning Satyagraha, stipulated it should be “a real opera.” In the ensuing decades, works including Robert Ashley’s stream-of-consciousness electronic operas and Helmut Lachenmann’s The Little Match Girl (1990) — which includes gasps, whispers, wails and almost every type of vocal utterance except the actual singing of text — further tested the boundaries. Recent works of musical theater, such as Michael Gordon and Deborah Artman’s avant-garde, heavily amplified Acquanetta, and David T. Little and Royce Vavrek’s engrossing Dog Days, which culminates in a deafening, apocalyptic drone, have rendered the borders of opera even more porous. These latest paradigm-shifting works, commissioned by independent companies that have made eclectic and experimental works their lifeblood, have created new opportunities in the broader opera world and the chance to attract a new audience to the art form.

Adventurous small companies, like New York’s Experiments in Opera and Heartbeat Opera, and Los Angeles’ The Industry, have proliferated in the last few years, often acquiring the labels “indie,” “independent,” “alternative” or “grassroots.” The most visible of all may be Beth Morrison Projects, which brings indie works to stages across the country, and commissioned the chamber version of Acquanetta that premiered at the most recent Prototype Festival in New York. Morrison herself says that after performances of works she has commissioned, she often hears audience members, particularly younger ones, say: “I didn’t think I liked opera, but if this is opera, I really like this.”

“New listeners are compelled by the kind of productions we do, which are contemporary in all ways, including staging and what they sound like,” says Morrison. “There is a connection to an audience that has grown up with a very visual world. I personally have no use for the powdered-wigs-and-knickers staging of anything. Nothing in my world connects to that in any way.”

Morrison says that the definition of opera in her world is very broad, noting that out of some 50 projects she has produced, about 45 have been amplified. There is a generation of composers who prefer an amplified sound world, she says, adding that using amplification can provide “an opportunity for more nuanced acting.” Even within the independent opera scene, there is certainly a huge aesthetic spectrum: The 2018 Prototype Festival, for example, included both Acquanetta and the much more traditional Fellow Travelers by Gregory Spears and Greg Pierce, which had its premiere at Cincinnati Opera in 2016.

“Indie” outfits now often collaborate with venerable companies such as Opera Philadelphia and LA Opera, which has partnered with Beth Morrison Projects and staged pieces like David T. Little’s Soldier Songs at the performance space under Disney Hall called REDCAT. There’s no hard data about whether grassroots opera has inspired fledgling fans to buy tickets to mainstream productions, just as it’s unclear whether HD broadcasts have ushered any new listeners into the opera house. But in any event, for Christopher Koelsch, president and CEO of LA Opera, ensuring a crossover audience between avant-garde and mainstream opera is beside the point: It’s a goal he views as “overly transactional.” Although he doesn’t make it a priority to convince an Acquanetta audience member to see Norma, he says he’d like to break down the firewall: “I’m looking for a fluidity in which people understand that there is a direct connection between the two works.” LA Opera offers subscription packages that include both contemporary works and mainstage productions.

“LA Opera was born of the idea that the art form was changing and that there is a class of composers whose work spoke to questions of what opera is, and what the canon is,” says Koelsch. “So how could the LA Opera become deeply involved in that conversation? It’s about what an opera company does. Who is it for? How can we combat people’s prejudices against opera? I am an evangelist for the art form and am interested in how Glass connects to Monteverdi. That is what the process is about.”

“The more people there are thinking about and making and producing opera, the better it is for the art form, because it encourages ideas to flow at a quicker pace,” says Elizabeth Cline, executive director of The Industry, the ironically named company founded by Yuval Sharon, best known for the “mobile opera” Hopscotch, in which listeners were driven in limousines and experienced the music both inside the vehicles and at different sites around LA. Alex Ross in The New Yorker described Hopscotch as “one of the more complicated operatic enterprises to have been attempted since Richard Wagner staged The Ring of the Nibelung, over four days, in 1876. ... It is a combination of road trip, architecture tour, contemporary-music festival and waking dream.”

I never heard someone say, ‘I liked Hopscotch so much I had to get a ticket to Carmen,’” Cline notes. But she nonetheless sees an alignment between The Industry’s offerings and traditional opera. “The music and the voice are the primary driver and experience of opera,” she adds. “When I want to defend our work as opera, I go back to that. It’s about these things coalescing and the alchemy of these mediums coming together.”

Experiments in Opera, launched in Brooklyn in 2010 by composers Aaron Siegel, Matthew Welch and Jason Cady, has commissioned 62 new works from40 composers in six years, under the premise that a composer’s imagination can be unleashed in creating work for a small institution in ways that large-scale commissions might stifle. Siegel notes that “hard-core traditionalists” are unlikely to sample EiO’s offerings — and when they do come, they tend toward a “seething rejection” of the company’s work. “We are avant-garde, and we wear that as a badge of honor,” he says. “We’re doing something good — we’re pissing people off!”

Last fall, Opera Philadelphia undertook an experiment that certainly paid off: the inauguration of an annual festival in venues around the city. O17, the first installation of the festival, featured three world premieres, including Daniel Bernard Roumain and Marc Bamuthi Joseph’s genre-bending We Shall Not Be Moved. The company has been lucky, according to General Director David Devan, “to knit the indie scene into our overall practice,” which he believes has helped revitalize its work in the core repertory: “Working with people outside your normal reality strengthens your artistic muscle. We’re not chronically updating things unnecessarily, but we want to speak to people today and create work that looks like it’s produced in the 21st century and build that kind of DNA into the company.”

Opera Philadelphia has found success in attracting audience members to mainstage performances after they attend contemporary productions in smaller venues, according to Devan. “It’s an onramp for new opera buffs,” he says. “This idea that indie opera is just for people with wool hats is an overly limited view — it isn’t just for the cool kids. Our understanding is that our world is a multi-channel universe and we want to provide as many ways as possible to experience the art form.”

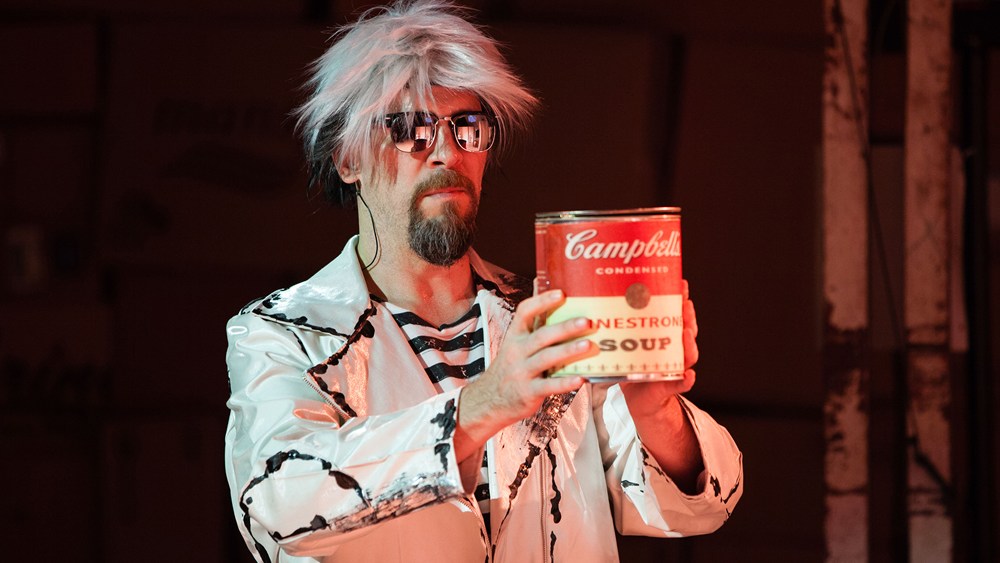

When he evaluates what can be considered opera, Devan imposes two criteria. The first is the requirement of a classically trained voice. (Cline also notes that, with the exception of Hopscotch, The Industry always hires classically trained singers.) Secondly, the music, whether electric or acoustic, has to serve a dramaturgical purpose. Nonetheless, Devan’s categorization of “opera” is of course often challenged: David Shengold, writing in Opera News, described ANDY: A Popera, a co-production between Opera Philadelphia and a local cabaret troupe, as “more music theater than traditional or even untraditional opera.”

Boundary shifting in opera isn’t limited to new work. Consider New York-based Heartbeat Opera, which this May offered a Don Giovanni with #MeToo overtones and a Black Lives Matter staging of Fidelio featuring videos of prison choirs singing the Prisoners’ Chorus. Director Louisa Proske, who co-founded Heartbeat with Ethan Heard, believes her company’s way of operating — more agile, less hierarchical and less compartmentalized than larger organizations — can have a positive impact on the opera industry as a whole. “We want to offer ideas for how to produce opera on a smaller budget,” she says. “It’s our deep hope that [indie and mainstream opera] flow together. We as directors want to work on bigger stages, as well, so hopefully there will be a cross-pollination of ideas.”

Making opera appealing to new audiences through stripped-down, radically reimagined productions is a matter of “thinking about entrance barriers and dealing with them,” according to Proske. “It doesn’t mean that you have to do away with five-hour operas,” she says. “But for newcomers, it can be helpful to see a reimagined 90-minute Carmen. They then realize that the voices are amazing and they want to experience it again.” Heartbeat is also working to expand opera’s audience through its “Halloween Drag Extravaganza.” “It’s a gateway drug for opera virgins,” says Heard. “Hopefully they fall in love with it and come back to our mainstage festival.”

Whenever a company presents an opera, Christopher Koelsch jokes, “someone will think you’re a genius and someone will think you’re an idiot — and they’ll both let you know.” More seriously, he asks: “What is the purpose of the art form in the end? The catharsis that comes with the ability to express the inexpressible. And it’s good that the tools to do that are expanding.”

A Concert Turns Theatrical

Pittsburgh Symphony has had recent success with fully staged versions of traditional concert works.

This article was published in the Summer 2018 issue of Opera America Magazine.

Vivien Schweitzer

Vivien Schweitzer is the author of A Mad Love: An Introduction to Opera.