Joined Forces

The challenges and rewards of co-productions

When Tomer Zvulun became general and artistic director of The Atlanta Opera in 2013, the company used sets and costumes rented from other companies’ moribund mountings. Five years later, Atlanta is mounting a season that, while still staying within budget constraints, much more thoroughly bears its own imprint. In fact, two of its mainstage shows, Dead Man Walking and Eugene Onegin, will be directed by Zvulun himself; those, along with La traviata, will be co-productions, put together by consortiums of companies that share costs and creative input.

A look at the 2018–2019 season shows that co-productions are a dominant force in our era. Two of the Met’s four new stagings will be co-productions; at Lyric Opera of Chicago, they make up more than half the season. Companies across the country — and indeed, the world — are finding that co-production partnerships, if they’re prudently administered, make sense from both an economic and an aesthetic standpoint.

In a time that places increasing emphasis on innovation in opera, co-productions allow companies to offer productions that, while they may not represent cost savings over rental arrangements and revivals, offer the advantages of both novelty and sophistication. If it were acting as a lone operator, The Atlanta Opera would never be able to present a season resembling its 2018– 2019 roster, which will give its audience a series of fresh experiences, on a scale more lavish and complicated than what the company might have been able to offer on its own.

With new works, a co-production will often be a co-commission, as well, with companies sharing the risk — and the glory — of bringing a new opera to the stage. But many companies now feel that the standard repertoire, too, demands the level of innovation that co-productions can afford. “It is incumbent on us to give our audience dynamic productions of standard repertory,” says Deborah Sandler, general director and CEO of Lyric Opera of Kansas City. Her company is lead producer on Zvulun’s Onegin production, in a consortium that, aside from The Atlanta Opera, also includes Hawaii Opera Theatre, Michigan Opera Theatre and Seattle Opera.

“If no one makes new productions, we’ll all be looking at productions that are 25 years old,” says Aidan Lang, general director of Seattle Opera. Making good on his observation, all five of his company’s 2018–2019 offerings are new to Seattle, and four of them are co-productions.

A co-production is, first and foremost, a business arrangement, and all partners need to stay focused on the bottom line. “In reality, what we’re looking for is money — people to share the cost,” says Abby Rodd, director of production at The Glimmerglass Festival.

On the face of it, the math is simple. “Say you’re spending a hundred thousand for your set and another organization is spending another hundred thousand,” says Sandler. “You get more bang for your buck.” When Opera Philadelphia was planning its recent Carmen, it was looking at a design and construction budget in the $500,000 range. But when Seattle Opera and Irish National Opera came on board, its own costs fell to roughly $200,000.

“If we’re doing a show alone, it might cost $400,000 to produce it,” says Karen Quisenberry, chief production officer at Minnesota Opera. “But if we get people to buy in, we can maybe make a $550,000 show and jazz it up a little more.”

“We live in a world that is looking for efficiencies, and a co-production is one of the few ways we can find them,” says Kurt Howard, OPERA America’s director of programs and services.

The savings that co-productions offer may be real, but they’re definitely finite. For one thing, hard production costs typically represent about 60 percent of a show’s budget. A company must rely on its own resources to meet the other 40 percent, covering personnel, along with marketing, ticketing, shipping and a host of other expenses. And even though the price of joining a partnership will be considerably lower than forging a solo path, it will probably not represent cost savings over a rental. “It may not cost less, but they can get more for what they’re paying,” says Howard.

Despite the cost efficiencies offered by a co-production arrangement, it does involve its own set of financial obstacles. All the partners have to put up their shares at the very outset; in some cases, years before the production makes its way onto the stage—and into the season budget. The partner companies need to find a way of finding funds for that carried expense.

Once a co-production has made the rounds of its home stages, its sets and costumes can be rented out to other companies, with the partners sharing in the revenues according to a schedule worked out in the initial negotiations, with junior partners, of course, getting a smaller cut. Case in point: Francesca Zambello’s staging of West Side Story, a Houston Grand Opera/Lyric Opera of Chicago/Glimmerglass co-production that will make its way to Atlanta next season in a rental agreement.

Future revenues will often depend on how well the show is received in the first place, and how much a market there is for the title. Glimmerglass spent a relatively lavish amount to join the West Side Story consortium, with the expectation that the show would have legs as a rental property. But demand — and back-end profits — can be unpredictable. If a show is a flop in the first place, it’s unlikely to generate much rental interest. Meanwhile, the fees that these rentals generate do not represent a total profit. The company that holds the sets and costumes charges the consortium for storage, handling, maintenance and restocking. All of these costs come off the top before the money is split.

Still, the rentals do hold the promise of recouping investment to some degree, even if a show is only rented once in a while. “At the end of the year,” says Quisenberry, “when you sit down and you’re going through everything, and suddenly you get a check for $12,000 or $13,000, it offers some fiscal relief.”

At their inception — before numbers start getting crunched — these arrangements often begin informally: when company directors chat on the phone, mingle at premieres or meet each other at the Co-Production Marketplace during OPERA America’s annual conference. “So much of this comes down to networking,” says David Levy, senior vice-president of artistic operations at Opera Philadelphia. He cites the genesis of a Nozze di Figaro as an example: “We knew Deb Sandler in Kansas City had Figaro on her radar screen,” he says. “And then we started talking to David Bennett in San Diego about his plans. It turned out to be easy to combine resources.”

When the first interested companies have identified each other, the originating company invites prospective partners to a design meeting, in-person or via videoconference, where the creative team lays out its pitch. Potential collaborators get a sense of the show’s tone and ambitions and may make their own suggestions. Ultimately, they decide if they want in on the action — either as full partners splitting costs equally, or as junior partners. In the case of Figaro, Palm Beach Opera also climbed on board. Lyric Opera of Kansas City took on the task of building sets and costumes.

San Francisco Opera, Seattle Opera and Washington National Opera had already agreed on a new Zambello Aida when Minnesota Opera signed on in 2017. “They needed a hundred thousand more,” says Quisenberry. “We had been bandying about the idea of doing Aida, but it’s such an expensive piece. This gave us the opportunity to commit to the idea.”

A co-production scheme requires meticulous preparation. Chief among the practical considerations is the physical space: Stages come in all shapes and sizes. Some are raked; others are flat. The show will have to be adaptable to each venue, with the physical dimensions of the participants’ stages and backstage areas determining the production design. (Opera lore is full of examples of co-productions that have been eviscerated in the transfer to too-small venues.) Seattle Opera seeks to prevent that from the outset, looking for partners with a proscenium roughly the size of that of McCaw Hall, between 50 and 60 feet wide.

Personnel arrangements can also cause divergences among partner companies. Some employ larger choruses; others may have unique labor agreements. Glimmerglass uses non-union labor, so when a show moves to a company with a union crew, the differing labor situations have to figure into the planning. “It takes more people and more time everywhere else,” says Abby Rodd.

A crucial factor in a co-production arrangement is that the partners should share an artistic vision. This is considerably harder to define than brass-tacks financial matters, but a sense of history helps — an institutional or personal connection that may already be in place. So does a shared artistic vision: A company that wants a Carmen on the moon is not going to collaborate with one that wants a cigarette factory and a bullring. “One tends to gravitate toward a house that shares a similar view about what opera should be,” says Aidan Lang. “It’s great to have a shorthand with your partners so that the conversations are easy and direct.”

A partnership may not work as planned, especially when it comes to the delicate matter of budgets, which can run into overages. In general, the lead company is responsible for budgetary matters. “If I pull together a consortium and we’ve all agreed on what the budget should be and it goes over,” says David Levy, “then I’m on the hook for it.” Originators may ask their partners for relief, or arrange to take a bigger share of ownership, or make up the overage later during the rental period.

Subsequent companies may also run into unexpected expenses. For example, some companies like to double-cast roles, requiring twice the number of costumes of their peers. If they look for compensation, the rule of thumb is: It better be in the contract. If not, says Sandler, “the answer is usually ‘no.’”

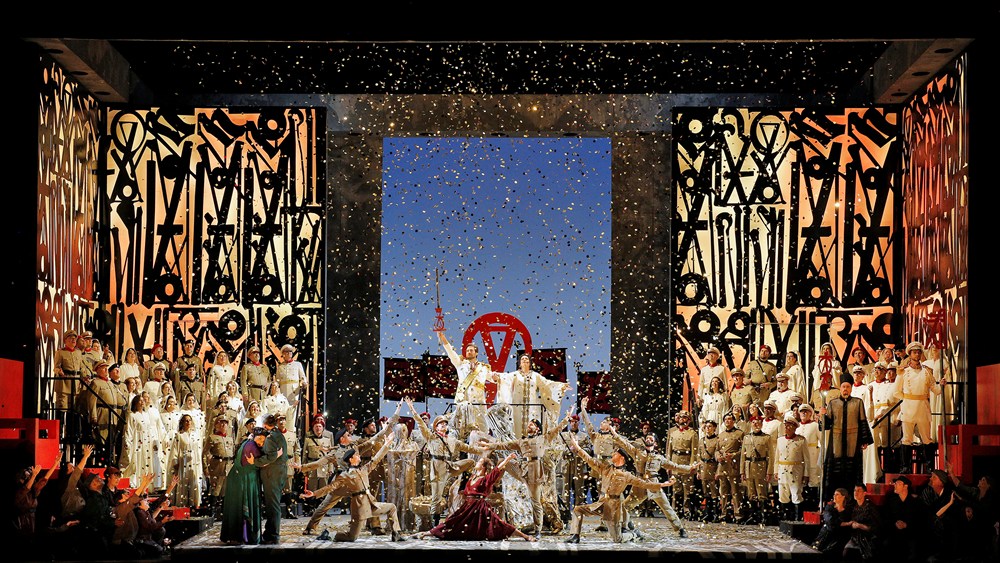

Sometimes expenses go up for secondary productions, but often because the company wants to do more with the show. For example, the Zambello Aida that started in San Francisco got a whole new dance sequence when it moved to Washington National Opera. Then, it got additional props for the triumphal march when Seattle Opera took its turn. In cases like these, the company making the changes pays for them.

The process can be even more extreme with a new work, which may undergo changes as it moves from venue to venue, much as a Broadway show in days gone by would morph as the creative team would hammer out its kinks on the road. The Santa Fe premiere of The (R)evolution of Steve Jobs made librettist Mark Campbell realize he needed to beef up the role of Laurene Powell, the title character’s wife. He has revised the ending of one scene and written a whole new one for the character: changes that he will work on with his collaborators, composer Mason Bates and director Kevin Newbury, as the work moves to Indiana University, Seattle Opera and San Francisco Opera.

Campbell notes a co-production arrangement can keep a work from vanishing after its premiere. “An opera has a better chance of entering the repertory if several mountings are lined up before it opens,” he says. “It can also be less dependent on critics’ approval to become a success.”

Given the ongoing pressures that all opera companies face, co-productions demonstrate not simply case-by-case pragmatic arrangements, but an overall understanding of the need for cross-industry cooperation. “Everybody in the industry realizes that we are in it together,” says Levy. “The more we share resources, the better off we will be as a whole.”

This article was published in the Summer 2018 issue of Opera America Magazine.

Ray Mark Rinaldi

Ray Mark Rinaldi is a veteran arts writer and critic whose writing has appeared in Opera News, Chamber Music, Inside Arts, and the Denver Post.