The Languages of Opera

Theatergoers think twice about attending a performance in a language that is not their own; for opera audiences, that is the norm. The standard repertoire is heavily weighted toward works in Italian, German, and French. Following the widespread adoption of titling systems in the early 1980s, nearly all U.S. opera companies now perform operas in their original languages with English supertitles. The repertoire does, of course, include some works with English-language librettos, and the expanding interest in presenting new opera has resulted in an even larger body of English-language works.

However, as opera companies start to think more broadly about their audiences and how the art form can be more accessible to more people, new discussions about language have begun. In recognition of the substantial Hispanic and Latinx-heritage population of the U.S., more Spanish-language operas are being presented. Creators are making artistic choices to write operas in nontraditional languages. Advances in technology mean that titling systems are not limited to a single language and can be customized based on individual communities. The pandemic has also produced some reckonings about access, and the ease and success of using multiple titling languages on the digital offerings created over the last two years has led organizations to expand those options in live performance.

Opera in Spanish, Hawaiian, and More

For some companies, considering language for Latinx audiences is nothing new. Florida Grand Opera has used bilingual Spanish and English proscenium titles since 1999, and the company has a substantial library of specially commissioned Spanish translations. “English is on the left, Spanish on the right,” says Susan Danis, the company’s general director and CEO. “We have long-time subscribers who insist on seats on the right because they prefer the Spanish titles.”

For the 2022–2023 season, Danis has gone one step further: a Spanish adaptation of Domenico Cimarosa and Giovanni Bertati’s Il matrimonio segreto. Danis got the idea in a beauty salon, where she overheard the squabbles of a Cuban family getting ready for a wedding. She enlisted Puerto Rican-born director Crystal Manich to trim and adapt the story, aided by “a Cuban American posse of women of different ages to get the right cultural sensitivity.” Reworked as a tale of entrepreneurial Cubans in Miami Beach in the 1980s, the opera, given the slightly altered title El Matrimonio Secreto, was translated by Dominican conductor Darwin Aquino and Italian mezzo-soprano Benedetta Orsi.

A handful of original Spanish-language operas, such as Mexican composer Daniel Catán and Marcela Fuentes-Berain’s Florencia en el Amazonas and Astor Piazzolla and Horacio Ferrer’s tango opera María de Buenos Aires, have also become go-to pieces at some U.S. companies. General Director David Bennett mounted both at San Diego Opera in 2017. He explains that when the company almost closed back in 2014, “the community stood up and wanted the opera to be here, so when I arrived, I thought about how we could welcome all of the community.” Spanish-language opera was an obvious choice in this majority-minority community.

San Diego Opera also has presented mariachi operas, a project that started with Houston Grand Opera’s commissioning of Cruzar la Cara de la Luna by Jose “Pepe” Martínez and Leonard Foglia in 2010. The production has been successful in numerous communities around the U.S. San Diego co-commissioned the third piece in the series, a Christmas-themed story called El Milagro del Recuerdo.

In October, San Diego will present the world premiere of Gabriela Lena Frank and Nilo Cruz’s El Último Sueño del Frida y Diego. The screen of its current titling system is too small to allow for bilingual supertitles, but Bennett hopes to invest soon in a new system that will have more capacity. The majority of Spanish speakers who attend performances are bilingual; however, Bennett says, “We’ve learned that Hispanic people feel more respected and connected to organizations that acknowledge the Spanish language.”

Creators are finding it easier to write and produce operas in nontraditional languages. Back when Josh Shaw, now the artistic director of LA-based Pacific Opera Project, was singing Pinkerton in Madama Butterfly, he started wondering how Pinkerton and Cio-Cio-San communicated, since they did not share a language. In April 2019, the company presented the opera in translation, with characters singing in English or Japanese depending on their background. (Shaw did the English text; Eiki Isomura, the conductor and artistic director of Houston- based Opera in the Heights, the co-producing company, did the Japanese.)

For Shaw, the love duet in particular took on a new dimension. “You could see how they are trying so hard to communicate these feelings while speaking words the other doesn’t understand,” he says. “It helps you see Pinkerton’s side a little bit — he’s not just grabbing the girl and taking her to the bedroom.”

The production had Japanese singers playing all the Japanese characters and chorus (the one exception was Cio-Cio-San’s Malaysian cover, who went on for several performances). The show sold out all three LA performances in the 850-seat Aratani Theater at the Japanese American Cultural and Community Center; 25 percent of the attendees were Japanese.

A portion of the libretto of Missing, an opera by librettist Marie Clements and composer Brian Current, is in the Indigenous language Gitxsan. During this year’s OPERA America New Works Forum, mezzo-soprano Marion Newman, who sang and created the role of Dr. Rose Wilson, shared her view of the role the opera played in helping to preserve the threatened language.

“This is a language that we would never have the opportunity to hear unless we happen to be in the territory where people still speak Gitxsan. To be able to sing that into the air, beauty of that language through music, is a wonderful way to let people know why it’s so important that we continue to work really hard to preserve what languages haven’t been lost completely yet.”

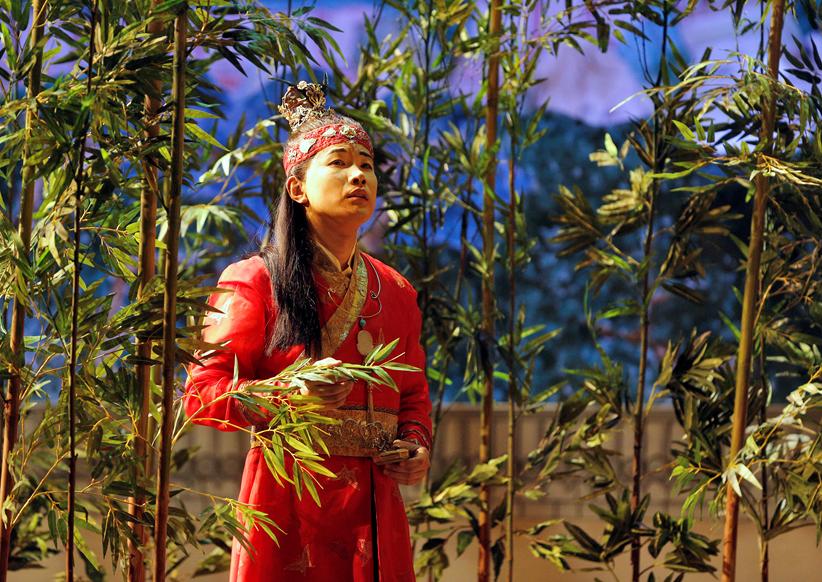

In Hawai‘i, the Big Island campus of the Kamehameha Schools has produced several large-scale operas, composed by Herb Mahelona, with librettos in Hawaiian that are based on traditional Hawaiian stories. The student-performed operas have even made their way to the Edinburgh Fringe Festival, making a connection even though few members of the audience in Scotland understood Hawaiian. Similarly, Huang Ruo’s Book of Mountains and Seas, recently given its U.S. premiere in Brooklyn, had a powerful impact while being sung in Chinese with only minimal English supertitles.

Show, Don’t Tell: The Role of Supertitles

Supertitles revolutionized access to opera nearly four decades ago. Now that American opera companies are grappling seriously with the idea that the audience is not necessarily a monolithic English-speaking group, titles can help further bridge the gap. Opera de Montreal, located in a bilingual city, has long offered both English and French proscenium titles, and many European houses and festivals offer English in addition to their home language. In the U.S., Florida Grand Opera is one of the few companies to routinely provide projected bilingual titles. However, Danis says it is starting to get requests to rent its Spanish titles from other companies.

Some companies use multi-language supertitles for particular repertoire. San Francisco Opera is reviving Bright Sheng and David Henry Hwang’s 2016 Dream of the Red Chamber, which is in English and based on a famous Chinese novel. The show is again titled in both languages, with English above the proscenium and Chinese projected vertically on the sides of the stage. The program used to project the titles, TitleDriver, was created by San Francisco Opera’s audio engineer, Tod Nixon, and designed to provide a very flexible platform. “One of the key features from the beginning was the four-column approach for providing multiple languages simultaneously,” he says.

This fall, Alliance for New Music-Theatre will premiere Rosino Serrano’s On the Road to Arivaca. For this bilingual Spanish and English opera, the company plans to use supertitles in both languages “so that different audiences can follow along as the singing switches back and forth,” says Artistic Director Susan Galbraith.

Companies with seatback titles (The Metropolitan Opera, The Santa Fe Opera, Opera Colorado, Lyric Opera of Kansas City) have the advantage of allowing patrons to choose their preferred language, rather than having to shoehorn multiple translations onto a screen above the proscenium or hang multiple screens. (The Met’s customer service department will also connect non-English speakers with a translator for box office and other requests.)

Mobile technology also provides this option. On Site Opera, which stages performances in nontraditional venues that make the usual title projection methods awkward, first experimented with cell phone titles when it staged Amahl and the Night Visitors by Gian Carlo Menotti in New York’s Holy Apostles Soup Kitchen in 2018.

On Site Opera’s general and artistic director, Eric Einhorn, says that the success of the Live Note technology used for the mobile titles (which was funded by an OA Innovation Grant) encouraged him to expand the language offerings. “It’s part of our ongoing self-audit as an organization, looking at what we are doing to make the art form as accessible as possible,” he says. “Titling only in English makes it exclusive, especially in New York.”

The revival of Amahl in 2019 thus offered Spanish titles, in a specially commissioned new translation, as an option. “This was a community-focused production, and Spanish is the second-most spoken language in New York,” Einhorn says. “As I was skulking behind the audience, I saw a healthy combination of English and Spanish on people’s screens.”

Murasaki’s Moon (composer Michi Wiancko, librettist Deborah Brevoort) was produced in the Astor Chinese Garden Court at the Metropolitan Museum in tandem with a large exhibition of Japanese art and artifacts. It was titled in English and Japanese to accommodate the expected Japanese audience. Einhorn was encouraged by the results and impressed by the quality of the images: “On the Live Note computer screens, the Japanese characters were clear as day, and easy to load.”

On Site’s spring 2022 production of Gianni Schicchi offered titles in Italian, English, and Spanish. “We hope that through offering Schicchi titles in Spanish, we can get some hard numbers and evaluate what languages we can use to reach people we haven’t reached yet,” Einhorn says. “It’s a relatively small expense to do these things. I think it might be that little tipping point for a person who wants to go to the opera, but English is not their first language.” For its next step, the company is looking at titling in the six UN languages: Arabic, Chinese, English, French, Spanish, and Russian.

The switch to digital production during the pandemic also resulted in some new thinking regarding language. Opera San Jose provided subtitles in English, Spanish, and Vietnamese for its numerous digital releases — the latter two representing the majority non-English languages spoken in Silicon Valley. “Our then-general director, Khori Dastoor, felt strongly about accessibility issues and saw OSJ’s digital season as an opportunity to expand access and cultivate stronger relationships within our community, and the trilingual subtitle options were an important part of this initiative,” says Artistic Projects Administrator Andrew Elsesser.

For the 2021–2022 season’s West Side Story, OSJ used side-by-side English and Spanish supertitles. While this choice was largely due to the themes of the piece, the company is “moving in the direction of providing English and Spanish supertitles for all of our productions next season,” Elsesser says.

The Fate of Opera in English

So, what is the fate of opera in English translation in this environment? Much of the standard repertoire offered in translation in the U.S. tends to be directed at family audiences, such as Hansel and Gretel. Comedy and operetta, often slightly reworked for modern sensibilities, like the Metropolitan Opera’s latest Die Fledermaus, is another place where English translations are common. For the most part, U.S. companies perform operas in their original languages.

Perhaps the most notable exception is Opera Theatre of Saint Louis. When Andrew Jorgensen became general director of the company, which has prided itself on being an American holdout of opera sung exclusively in English (original or translation), he thought the policy might be ripe for review. “This company has taken on every controversial topic — Israel-Palestine, Kashmir, race. Surely opera in Italian isn’t the one issue we are unable to tackle.”

He changed his mind after experiencing the 2019 season during his first full year on the job. “I sat in the house every night and watched audiences respond. They laughed louder, at the right moments, and more immediately,” he says. He saw that response as evidence of OTSL’s success in its mission “to be the most accessible opera company in the country, presenting opera with the smallest number of barriers.”

Jorgensen notes, however, “One of our blind spots in the field is presuming that the language of the audience is English.” While OTSL has no current plans to alter the English-language policy, “If we were to consider doing some operas in other languages, Cruzar or Florencia, rather than Roméo et Juliette in French, would be the place to start.” At the same time, the kind of English used in its singing translations is under review.

He adds, “Our long-time patrons are incredibly proud of the tradition of continuing to do opera in English. We also know, through marketing data, that telling people the opera is in English is a huge step in removing anxiety about attending for the first time. That’s as convincing an argument as we can make in service of making sure opera remains vibrant for years to come.”

Austin Opera Receives Major Gift to Support Spanish Language Programming

In April, Austin Opera announced the largest gift in its history: a $3.3 million contribution from Austin philanthropists Sarah and Ernest Butler to support Spanish-language programming. Claudia Chapa, who curated the company’s Concerts at the Consulate series last year, was appointed the inaugural curator of Hispanic and Latinx programming and will ensure that Hispanic and Latinx programming is represented across all of Austin Opera’s artistic platforms.

The Butler Fund for Spanish Programming will support an expansion of Austin Opera’s artistic offerings in alignment with its commitment to share stories and musical experiences representative of the community. “Our collaborations with the Mexican Consulate have influenced the trajectory of Austin Opera in a significant way, and this generous investment from the Butlers will exponentially increase the scope and impact of our partnerships throughout the community,” said General Director and CEO Annie Burridge.

This article was published in the Summer 2022 issue of Opera America Magazine.

Heidi Waleson

Heidi Waleson is The Wall Street Journal’s opera critic and the author of Mad Scenes and Exit Arias: The Death of New York City Opera and the Future of Opera in America.