Dialogue in the Desert

While many North American opera companies have only recently started connecting meaningfully with indigenous people around them, the Santa Fe Opera has been building relationships with Native American communities in its home state of New Mexico for nearly half a century. That work has proceeded on two fronts: creatively, when the opera integrated Native American elements into its 2018 production of Dr. Atomic, and civically, in its dealings with the local Tesuque Pueblo, which had begun developing its land adjacent to the opera’s open-air amphitheater.

Santa Fe’s Pueblo Opera Program (POP), in existence since 1973, invites families from 21 pueblos and reservations to dress rehearsals of three operas each season, with the dual aim of sharing culture and building audiences over multiple generations. That long-standing connection morphed organically into an artistic partnership in 2018, when Peter Sellars mounted the Santa Fe production of Dr. Atomic, his Manhattan Project-themed collaboration with John Adams. Set at nearby Los Alamos National Laboratory, the opera details the detonation of the first atom bomb: an event that had a grave impact on the environment and the state’s native people.

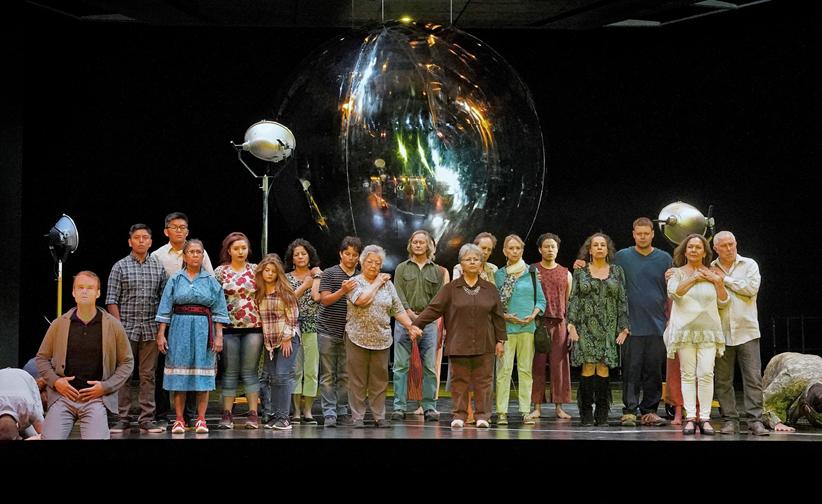

Sellars invited members of the Tularosa Basin Downwinders Consortium, which seeks justice for people harmed by radiation, to appear onstage. Meanwhile, a group of indigenous dancers offered to perform the traditional sacred Corn Dance for opera audiences. The dance served as a preamble to the opera; later on, in Act II, the dancers reemerged, performing the Corn Dance to Adams’ music.

The company’s discussions with the Tesuque Pueblo have been an entirely separate matter, although similarly showing the need for SFO to work with its indigenous neighbors. The pueblo’s land sits right at the foot of Opera Drive, and the opera company feared that the new development, with a casino at its center, might interfere with its own operations.

SFO’s history of working with local Native Americans gave the dialogue “a place to start,” according to Andrea Fellows Walters, the company’s director of commmunity engagement. But it was hardly a panacea. The company quickly learned that many community members nurtured long-simmering resentments, dating back to 1956 when John Crosby built his new opera house on land that the pueblo’s people had traditionally owned. Many local Native Americans saw the company as a manifestation of the westward expansion that had routinely ignored the rights and customs of indigenous populations.

The discussions have continued without any clear resolution. The opening of the casino in 2018, though, proved not to affect performances. In fact, SFO has been able to use the casino’s lot for overflow parking; moreover, opera patrons are actually heading down the hill to place bets.

As the pueblo plans for further building — including a possible performance venue — SFO remains concerned. But it is also working to repair damage from past practices, exploring ways to improve. The entire organization, from board members to administrators to artists, is exploring ways to improve its connections with its indigenous neighbors. These might include the development of new work revolving around native themes, along with finding ways to bring jobs and career opportunities to the community as a whole.

“This is the start,” Walters says. “Not the conclusion.”

This article was published in the Winter 2020 issue of Opera America Magazine.

Ray Mark Rinaldi

Ray Mark Rinaldi is a veteran arts writer and critic whose writing has appeared in Opera News, Chamber Music, Inside Arts, and the Denver Post.