The Oral History Project

On the occasion of its 50th anniversary, OPERA America embarked on an ambitious oral history project — setting out to record the recollections of 75 key figures who have shaped the American opera field over the past 50 years. Below are edited excerpts from some of the recently recorded oral histories. The complete oral histories will be made available in 2022 on OPERA America’s website. Support for this project was provided by the Arthur F. and Alice E. Adams Charitable Foundation.

Simon Estes, bass-baritone

An introduction to opera

“My teacher Charles Kelos discovered me at the University of Iowa in 1961 and worked with me for two years. But before he started working with me, he said, ‘Do you know you have a voice to sing opera?’ And I said, and this is really true, ‘What’s opera?’ Because I come from a small town: Centerville, Iowa. I had never seen an opera in my life. ... Mr. Kelos took me to the old Met, down on 39th Street. I saw Rigoletto with Cesare Siepi as Sparafucile, and then he took me to Don Giovanni with Siepi. And I tell you, I fell in love with that music.”

Facing racial discrimination

“I called my mother in the early 70s, in tears, and said, ‘You know, Mother, I’ve sung in many opera houses in Europe. They still won’t let me sing in America.’ And my mother said, ‘Remember what I taught you when you were a little boy; if you came home and a White boy had called you the N-word or hit you, what did I tell you? I said, “Get down on your knees and pray for that boy.” Now, you just get down on your knees and pray, Son.’ And after that, I sang at the Met, Chicago, San Francisco, Boston, Philadelphia, D.C. — all the opera houses in America. And I attribute it to my faith and the inspiration that my parents gave me.”

Breaking barriers at Bayreuth

“Wolfgang Wagner heard about this Black guy studying The Flying Dutchman [at the Zurich Opera House in 1977]. He wanted me to come and audition, and so I drove to Bayreuth from Zurich, sang the audition, and he said, ‘I want you to open the season next year at Bayreuth; a new production; the title role of the Holländer.’ ... The only other Black person who ever sang there was Grace Bumbry. Some of the press were going to boo that Black man off the stage — ‘He has no right to sing in Wagner’s Festspielhaus’ — this is really true. But you know, it didn’t make me angry. It didn’t make me scared. I had the contract to do it. And I sang it, and it ended up being a success in Bayreuth.”

Singing opposite Leontyne Price

“Margaret Price [who was scheduled to sing Aida at San Francisco Opera in 1981] got sick, and Leontyne had to jump in because she knew the role, of course. Leontyne had never heard me sing live. We were rehearsing in front of the whole cast, and in our Aida/Amonasro duet, she started crying. She said, ‘Simon, singing next to you is like singing next to a Black god.’ And the tears were going down her cheeks. I said, ‘Leontyne, no, you’re the one.’ She said, ‘Simon. No.’ I will never forget that.”

Anthony Davis, composer

The genesis of X, The Life and Times of Malcolm X

“In 1983, Mary McArthur (now Mary Griffin) was at The Kitchen, where I’d done some performances with my group, Episteme. ... She asked me, ‘Do you have an idea for an opera?’ And I said, ‘Yes, I do. And it was X. And that came about when my brother was an actor and was in a play performing the role of Malcolm X at Yale Drama. When I went to the play, my brother came backstage and he said, ‘You should write a musical about Malcolm X.’ And I said, ‘No, that’s an opera — he’s a tragic hero.’”

Revising X for its 2022 premiere at Michigan Opera Theatre

“When I wrote the opera, I was still thinking of creating a showcase for the jazz players in my band. To me now, it’s drama first — it’s always drama first. So what serves the drama? How would I best do that? By being more concise, more to the point, and still having improvisational moments, but making them count more and be more integral to the flow of the drama.”

Writing political works like The Central Park Five

“I remember fantasizing, when I first started in opera, that I was kind of a guerrilla. I always thought about this idea of being subversive in [the opera] world, because when I first went into it, I thought of opera institutions as being part of the elite, the establishment. But to go into that space and present things that speak about the power structure, and inequities, and what’s going on in the political world to me was a kind of a subversive act. And that was exciting to me because I was always looking for ways to be an activist with art — art could provoke and art could be provocative; art could also try to understand what underlies the political moment.”

The advice he gives to his composition students

“Don’t fail for lack of ambition. Sometimes my students say they try to think practically and think small. And so I say, ‘This is the time for you to really explore what your dreams are; what your voice is going to be. So don’t sell yourself short. Don’t say, ‘Well, I had to just write for one violin.’ It might be about instrumentation, but it’s also about the vision: seeing that the potential is greater than what they’re doing in the moment, that there’s something more they can find.”

Francesca Zambello, Artistic Director, Washington National Opera; Artistic and General Director, The Glimmerglass Festival

Beverly Sills at New York City Opera

“Beverly was very much a people’s general director. I always remember her standing on the steps, greeting people. And I, as a general director, always do that, because the personal touch is important, but you also learn your audience.”

Early mentorship from Jean-Pierre Ponnelle

“Sarah Billinghurst [then artistic administrator at San Francisco Opera] introduced me to Jean-Pierre, and I started working with him in Italy on a number of productions. ... From Jean-Pierre, I learned about directing people: characters, individuals. It’s a difficult part of directing. It can’t all be production; you have to get inside of characters. And even though he himself was a designer, he was so character-centric and driven by the music.”

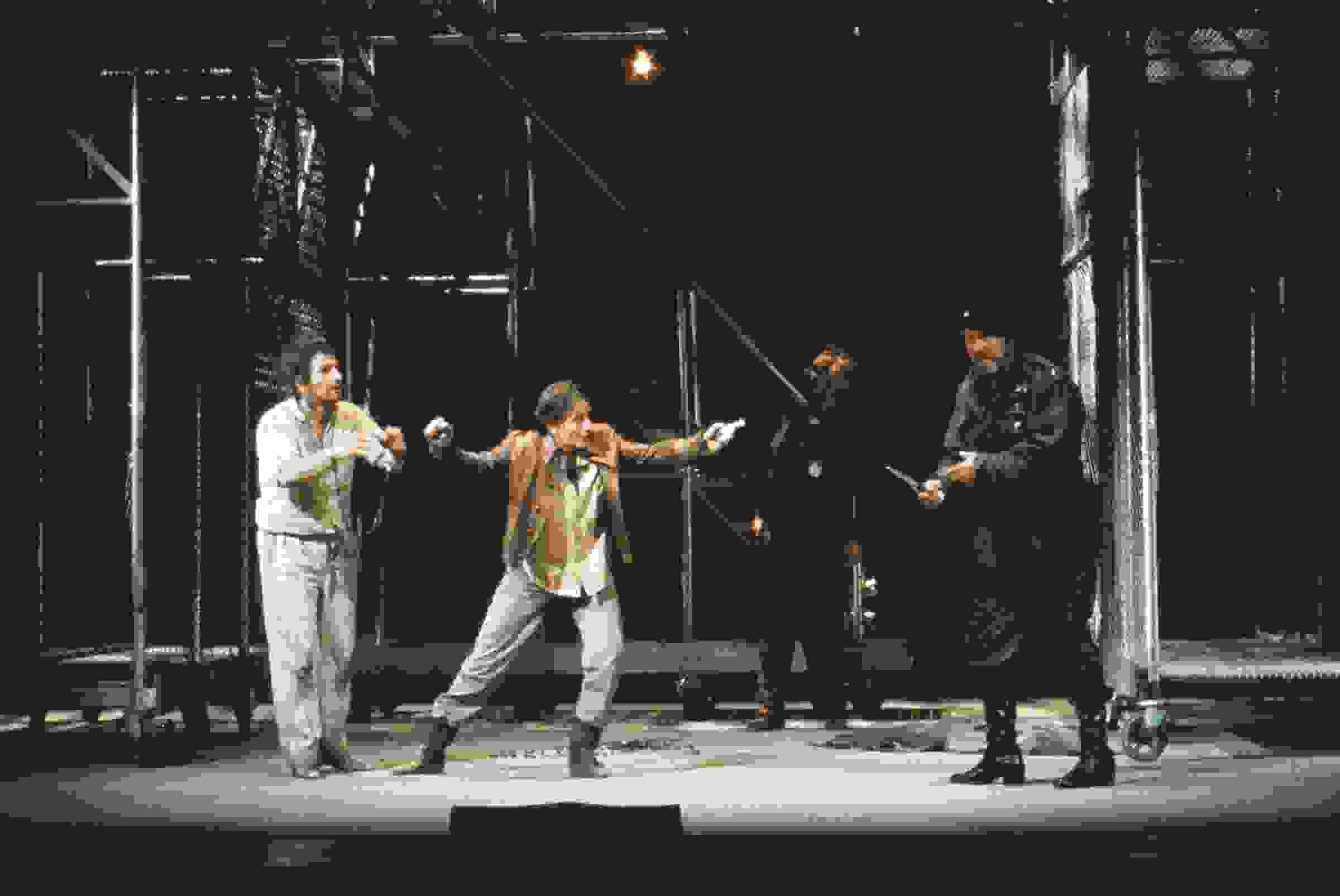

American directing debut in 1984

David [Gockley, general director of Houston Grand Opera] gave me Fidelio with Hildegard Behrens. He called me and he said, ‘I’m going to give you this amount of money’ — I think it was $25,000 — ‘to come up with a concept for a set and a production, and you have a week.’ America was involved in a lot of activity in Central America, and so the production was set there, and it was all chain-link fences and jeeps. ... The conductor was Michael Tilson Thomas, and so it was these two young people really breaking onto the scene and making a big statement with the Fidelio, and the production was incredibly successful. If you work in this medium, when the music and the singing and the drama and the production come together, it’s a high. We’re always looking for that high, and it doesn’t happen all that much.”

Met debut in 1992

“I made my Met debut with Lucia, which was, I would say, a rather revolutionary production — there hadn’t been booing and cheering like that in the Met in some time. It catapulted me into a lot of jobs in Europe, and many of the companies that hired me were run by women: Renée Auphan, Elaine Padmore, several women running Italian theaters in Parma, Bologna, Rome, and Pesaro.”

New American works

“In the 90s I really felt, we have got to be commissioning more of our own voice, our stories. And since then, I’ve worked on well over a hundred new works, pieces that have ranged from the Metropolitan Opera to these 20-minute jewels that we do at Washington National Opera. ... Helping create all these contemporary works that are about social-impact issues, like Blue [by Jeanine Tesori and Tazewell Thompson] — it’s realizing that opera can have a bigger voice; the ripples can be bigger.”

This article was published in the Winter 2022 issue of Opera America Magazine.