Live and In Person

In the midst of the pandemic, innovative solutions bring opera to live audiences.

The COVID lockdown in March meant the immediate shutdown of all live opera and a quick jump to online performances, some archival, some hastily improvised. However, as the months passed and restrictions began to loosen, North American opera company leaders started to think about when, where, and how it might be possible to have live performances for in-person audiences again. “Our big concern is staying connected with our audience,” says Christopher Hahn, general director of the Pittsburgh Opera. “Live performance is the anchor of what we do,” says Yuval Sharon, artistic director of Michigan Opera Theatre.

In early August, New Hampshire’s Opera North staged socially distanced outdoor performances at its Blow-Me-Down Farm; later that month, the Phoenicia International Festival of the Voice offered a drive-in performance of Tosca. Ensuing months saw a range of imaginative responses to the challenge from around the U.S. From a baseball stadium in Tulsa to a parking garage in Detroit, a circus tent in Atlanta, and a black box theater in Pittsburgh, opera producers embraced the limitations required by safety protocols and made something original.

To do so, they had to deal with a tsunami of entirely new issues. Foremost was safety — for the performers, crew, and audience — and a continually changing web of rules to ensure it. States, counties, and municipalities had varying requirements, as did the unions representing singers, players, and stagehands. Given the aerosol transmission of the virus, singing and wind playing posed special risks. Working closely with local health partners, each opera company produced detailed safety protocols for rehearsals and performances. These included everything from initial quarantines to daily health questionnaires and temperature checks to mandates about audience size and the distance between singers. Safety concerns determined what operas could be produced and how they would need to be modified. Operas were abridged and their orchestrations changed. Intermissions were eliminated.

With theaters remaining closed in many areas, companies explored outdoor options. In June, after the cancellation of its fall Rigoletto was announced, Tulsa Opera got a call from the owner of its city’s minor league baseball team, the Drillers, offering the use of their outdoor stadium. Tobias Picker, the company’s artistic director, considered building a stage but realized that the regulations for singer separation — 25 feet if singing toward each other; 10 if not — would require an impractically large amount of space. Instead, he invited director James Robinson to use the diamond itself as the set for a baseball-themed Rigoletto, with the title character as the team’s mascot. The score was trimmed to avoid intermissions, the orchestra pared to a piano sextet, and the cast and crew kept to a total of just 40 people. A jumbotron transmitted closeups of the singers and titles.

Tulsa’s single performance of Rigoletto attracted an audience of 1,800 socially distanced and masked patrons. Ticket revenue was comparable to projections for the originally planned two indoor performances; meanwhile, the production costs were lower. Novice operagoers attracted through the Drillers’ marketing turned out in droves. Concession stands were open, and sponsors enjoyed the special amenities of skyboxes. It was so successful that Picker hopes to do more operas in the stadium even after it’s no longer the company’s only choice.

The opera department of the University of Nebraska at Lincoln used a grassy courtyard for its production of The Cunning Little Vixen. Everyone was miked, and the orchestra performed inside the school’s recital hall lobby; the singers playing animals operated large puppets, which helped make the distancing requirements feel natural. The daytime schedule meant that the show could be done without stage lighting, though the start time was moved from 3:00 p.m. to 5:00 p.m. because of the early October heat. Even though rehearsals and coachings took place outdoors, as well, student performers kept their masks on — until the second tech rehearsal. “The sound guy said, ‘The masks have to come off if we’re going to do this the right way,’” explains William Shomos, the head of UNL’s opera program and the production’s director.

The city of San Diego would only permit large outdoor audiences if people stayed in cars, so San Diego Opera presented its already scheduled and contracted La bohème as four drive-in performances in October and November. Regulations for singer separation drove the production concept: Rodolfo, 10 years later, relived the story; he and Mimì stayed on separate platforms. David Bennett, the company’s general director, negotiated with the unions to eliminate the chorus and reduce the orchestra to 28 players. The sound-mixed performance was broadcast through car radios, and the stage and titles were also visible on screens. Tickets were sold by car (one person per seat belt allowed); ticket income for about 1,550 cars over the run totaled $600,000. Since the drive-in Bohème cost less than the planned indoor production, its bottom-line stayed within range of pre-COVID projections. In November, Pacific Opera Project also launched a drive-in opera season, in a Ventura County church parking lot, with an updated COVID fan tutte, set in a SoCal golf resort.

Other companies devised hybrid formats for production and chose their repertoire accordingly. Yuval Sharon wanted to launch his tenure as Michigan Opera Theatre’s artistic director with the sort of unconventional work that has become his trademark and opted to use MOT’s multistory parking garage. “I thought, what material would make sense to depict in that environment?” Sharon says. He knew that Christine Goerke might be free, given the cancellation of the Metropolitan Opera’s fall season, so he imagined her singing the Immolation Scene from Götterdämmerung in the garage. “That is exactly the kind of story we need to be telling right now — about a powerful woman tearing down an old world order that no longer serves, so something new can emerge. All of the darkness in that piece is served by the parking garage, and then it ends in a blaze of glory.”

The result was an hour-long drive-through adaptation called Twilight: Gods. Six of Wagner’s scenes, sung in Sharon’s English translation, were staged on different levels of the garage, each witnessed by eight cars at a time. The music was heard through car radios, with a different frequency for each scene. (There were four days of performances; either 12 or 14 cycles of cars attended each day.) Detroit poet Marsha Music wrote and recorded a connecting narrative. Arrangements with unique instrumentations were created for each scene, and Goerke, in a nod to the Detroit setting, drove off from her rooftop “immolation” in a Ford Mustang.

The cast and crew totaled 175 people, but because each scene was self-contained, rehearsals could be managed with minimal contact and efficiency. The singers and instrumentalists all wore in-ear monitors, which meant that they could keep their distance from their colleagues. The show will be remounted in April by Lyric Opera of Chicago.

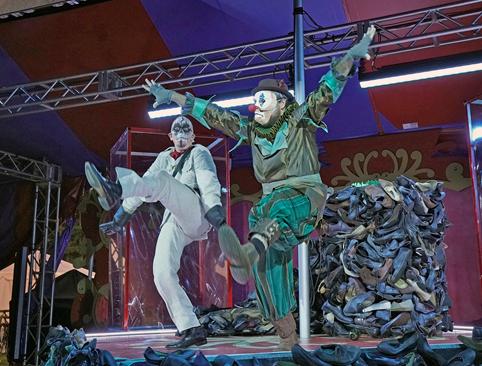

The Atlanta Opera’s live-performance undertaking was even more elaborate. In a custom-built, open-sided tent pitched on a university baseball field, the company mounted Pagliacci and The Kaiser of Atlantis, chosen, says General and Artistic Director Tomer Zvulun, because both depict the resilience and determination of artists in the face of adversity. The operas played on alternate days for 19 performances in October and November, with three concerts added into the mix. The tent could accommodate up to 240 distanced patrons; the circus-themed productions, directed by Zvulun, featured vinyl barriers separating performers at moments when they were not masked. The show was miked, and the pre-recorded Pagliacci chorus appeared as a Zoom grid. The operas were cast from the company’s young artists and the Atlanta Opera Company Players, a group of 12 major singers living in the area.

The planning took six months. “We prepared for everything we could imagine — weather, COVID outbreaks, noises that you can’t control,” Zvulun says. “I found [Nassim Nicholas] Taleb’s book The Black Swan very helpful — about how there are always things that you can’t plan for.” For Atlanta, one of those was Hurricane Zeta, which knocked over its orchestra tent; one Kaiser performance had to be rescheduled to allow the team to reconstruct it.

For companies that opted to produce live opera indoors, there were other calculations. Pittsburgh Opera planned a four-opera season at the George R. White Opera Studio, within company headquarters. The first show was Così fan tutte, with six performances in October, each with an audience of about 50 people. The operas were chosen with their forces in mind: Così could be cast with the company’s six young artists.

Given the small space, the singers had to wear masks while performing. Director Crystal Manich set the production in an Italian munitions factory during the flu pandemic at the end of World War I, making a mask an appropriate costume piece. The opera was trimmed to 90 minutes without intermission, and the 17-piece orchestra was placed behind the singers. After some experimentation, the final mask design had three layers of fabric over a plastic structure that kept cloth away from the nostrils and mouth.

Utah Opera also adapted its repertory plans, switching from The Flying Dutchman to an operatic double bill. Wendy Bryn Harmer, under contract to play Senta in the Dutchman, agreed to learn Poulenc’s La voix humaine (in English) instead. Artistic Director Christopher McBeth hit on Joseph Horovitz and Gordon Snell’s two-character comedy Gentleman’s Island as a good counterweight and negotiated a reduced orchestration with the publisher. Since the orchestra could not be in the pit, it was raised to stage level, and players were placed upstage, behind a scrim. The program received 10 performances in early October. Local regulations kept audience capacity in the 1,700-seat Janet Quinney Lawson Capitol Theatre at 15 percent; actual audiences ranged from 60 to 200 people.

Opera Memphis, Washington National Opera and Boston Lyric Opera have staged live concert performances, sending their young artists to various neighborhoods. These relatively small-scale operations required surprisingly complicated negotiations. WNO’s Pop-Up Opera Truck had planned a comprehensive tour in the District of Columbia, but after updated guidelines prevented it, the truck instead visited hospital parking lots, farmers markets, and other sites in neighboring Virginia and Maryland. The BLO truck had to limit its preregistered outdoor audiences to 35; more than 49 people, and the company would have needed to provide porta-potties. WNO also produced a solo recital by baritone Will Liverman in the Kennedy Center Opera House, placing the small, distanced audience on the stage and the performers on a platform built over the orchestra-level seats.

The elaborate safety protocols that companies have been taking seem to have paid off: So far, there are no reports of COVID infections stemming from operatic projects. Meanwhile, the performances are usually drawing enthusiastic, capacity audiences. Pittsburgh, Michigan, and Atlanta added performances to their original schedules; Sharon says that as the Twilight: Gods run proceeded, more people filled each audience car. Attendees at many of these opera performances told company representatives that these were their first COVID-era expeditions other than to the grocery store. They also reported that they had arrived with trepidation and left feeling perfectly safe.

For some companies, the live performances have generated a side benefit: digital versions that can be deployed to serve audience members who could not attend and sometimes generate additional revenue. Tulsa’s Rigoletto, filmed for the jumbotron, is now available for free on demand. Opera Orlando has made its December indoor production of Die Fledermaus available online, for a small fee. Pittsburgh Opera raised as much in donations from the Così livestream viewers as it got from ticket sales for the whole run. Atlanta Opera is offering its “Big Tent” shows as part of its new Spotlight Media digital subscription; in November, the company received a $500,000 grant to build its digital capacity.

In most of the country, winter weather will prevent outdoor productions, but in February, Palm Beach Opera plans a semi-staged, three-opera festival in a roofed stadium. Some summer festivals, meanwhile, have already announced outdoor plans. Opera Theatre of Saint Louis will perform outside on its present campus. The Santa Fe Opera, which has an open-air theater, will mount a 2021 season, but with four works instead of five. Such performances will, of course, be subject to changing safety protocols.

Not all live-performance plans have come to fruition. In November, an Allegheny County health advisory forced Pittsburgh Opera to cancel its plans for a December run of Soldier Songs with in-person audiences. Instead, the company livestreamed a single performance of the work. Similarly, Lyric Opera of Kansas City, faced with a shift in city restrictions, had to replace its planned eight-performance holiday run of Amahl and the Night Visitors with a pay-per-view online film.

For the companies that have offered live performances during the pandemic, the challenges have been worth it. For one thing, donors have been appreciative, and generous in making up the difference between costs and earned income. “Our major donors have mostly increased their giving,” says Christopher Hahn, Pittsburgh Opera’s general director. “I’m not sure that would have happened had we just gone silent.” Meanwhile, these efforts — in particular the outdoor shows — have attracted new audiences. Some Twilight: Gods attendees told Sharon that it was their first opera; they had come simply to savor live performance. At San Diego Opera’s Bohème, 32 percent of the ticket buyers had never before bought an opera ticket.

Live performances offer the additional benefit of providing work — and paychecks — for some of the thousands of artists and backstage personnel who have been sidelined during the pandemic. “We had 120 people in all, most of whom had not worked since March,” reports San Diego’s Bennett. “We fulfilled our contracts and paid the same value as we would have paid in the theater.” As anticipated, the drive-in Bohème lost more money than projected for the theater staging, but the company also pulled in about $190,000 in new contributed income.

The process of building something quickly from scratch has also demonstrated how adaptable and resourceful companies can be. San Diego, for example, secured county permission to proceed with Bohème just one month before rehearsals began. Yuval Sharon notes: “Leonard Bernstein once said, ‘To create something great, you need a great idea and too little time.’”

All in all, this season’s live performances have delivered rewards both operational and psychological. “It has been galvanizing for this company to come together, to deal with adversity,” says Atlanta Opera’s Zvulun. “As long as we can do it safely, the show must go on.”

This article was published in the Winter 2021 issue of Opera America Magazine.

Heidi Waleson

Heidi Waleson is The Wall Street Journal’s opera critic and the author of Mad Scenes and Exit Arias: The Death of New York City Opera and the Future of Opera in America.